Explore Counseling Today Articles

Deconstructing anxiety

I have always found it tremendously frustrating that our rational minds can’t convince us that most of our fears and anxieties are nothing to be afraid of. Many of my clients express the same frustration. As philosopher Michel de Montaigne said, “My life has been full of terrible misfortunes, most of which never happened.” Sadly, this is true for many of us, and no amount of positive thinking, affirmation or even cognitive transformation will touch any but the most superficial layers of anxiety.

In my early teens, I began a search for answers to this problem. It started with the questions that all good adolescents ask: Why are we here? Who am I really? What can be done about suffering? As a young man, this inquiry took me literally around the world as I met and had exchanges with a Zoroastrian high priest in Mumbai, a Zen master in Kyoto, fire walkers in Sri Lanka, and fakirs in Bali, as well as many of the leaders in the “consciousness” movement. One of my primary takeaways was that anxiety is fundamental in the human experience … and universally so.

This really caught my interest because I recognized the constant fear, sense of threat, and hypervigilance that seemed to be required to “survive” as not only overwhelming but as a fruitless way to live. Later, I channeled this interest into a career as a psychologist and devoted myself particularly to the study of anxiety. At some point in my search, I concluded that anxiety was not just fundamental, but the single greatest source of suffering in life — more central, even, than depression.

Over the years, my personal exploration and work with clients began to reveal certain repeating patterns about the fundamentals of anxiety. From this evolved a new model for treatment that has been gathering significant attention, not only for its effectiveness in treating anxiety but as a new therapeutic approach in general. It synthesizes several modalities, Eastern and Western, to deconstruct anxiety to its most elemental components. Positing a “basic anxiety” (cf. Karen Horney) as the underlying cause of our difficulties, the model pinpoints the precise moment and mechanism by which anxiety took root and altered our perception, creating a world of distorted and painful experience.

The model lays out what is in many ways a radically new understanding of the origin of anxiety, both in the individual and in the evolution of humanity. It describes the arrival of a “core fear” — one’s overriding interpretation of life as dangerous, and a “chief defense” — one’s primary strategy for protecting oneself from that danger. The core fear and chief defense create a singular dynamic that, according to the model, is the true wellspring of basic anxiety. Together, they open up a Pandora’s box of all our fear-based experiences, creating an anxious worldview.

The deconstructing anxiety model presumes that our original state of being is one of wholeness and fulfillment. But at a young age (and perhaps even in utero, as per Otto Rank’s concept of the birth trauma), we have our first contact with danger that establishes our core fear. Our mother leaves the room, and we think it is forever. Our father is distant and cold, and we are left wanting.

With the arrival of the core fear, we must choose a strategy for self-protection — our chief defense. This strategy, because it assumes “something out there is against us,” has us see ourselves as separate from the whole — from others, from what we need, from fulfillment. Armed with our chief defense, we embark on a quest to reclaim our original well-being.

Because this quest is motivated by fear (the fear of being separate from what we need), it can never succeed: With our focus on avoiding fear, our attention becomes consumed with all of the dangers that might sabotage our search. In this way, the core fear and chief defense become the original cause and perpetuator of our unhappiness. As a strategy to protect us from danger, they project our fears onto reality so that we may be “prepared” for them. This projection creates what I like to call a three-dimensional, multisensory hologram — a living, breathing perceptual distortion based on anxious premises. The great problem of human suffering is that we forget this is only a projection and take the hologram to be “real.”

Combining insight and action

What to do about this very human predicament? According to our model, we must thoroughly deconstruct our anxiety down to the core fear and chief defense that created the trouble in the first place. Only then can we see that they are made up of learned constructs, built from childhood assumptions that no longer serve us.

This sounds ordinary enough, but the model completely redefines what it means to perform such a deconstruction. It is only when we arrive at the “root of the root,” the original “mistake” in thinking (again, both in the individual and in humanity as a collective), that we can truly achieve the insight to show us that our fears are not founded. This depth of insight is rare. So often, we are mystified about why we suffer; despite our best efforts and insights, we become lost in the catacombs of unconscious fears, with no sure compass to direct our course.

Even if we do achieve true insight into the original thought of fear at the root of suffering, we may still need, as neuroscience shows, to take corrective action if we are to truly resolve anxiety. This is because fear can get written into our physiology in ways that insight alone cannot heal. Finding the correct action to take that will truly expose the illusion of our fear can also be challenging.

So, the right combination of insight and action is our goal. For this purpose, the deconstructing anxiety model has developed two powerful techniques that quickly reveal one’s core fear and chief defense. These diagnostic tools cut through our confusion and explain the original source of our suffering with comprehensive insight. Such insight suggests the necessary tools for action (also given in our model) to resolve the problem. Taken together, these practices help one get “behind the camera,” so to speak, that is projecting our individual and collective worlds of anxious perception.

Finding the core fear

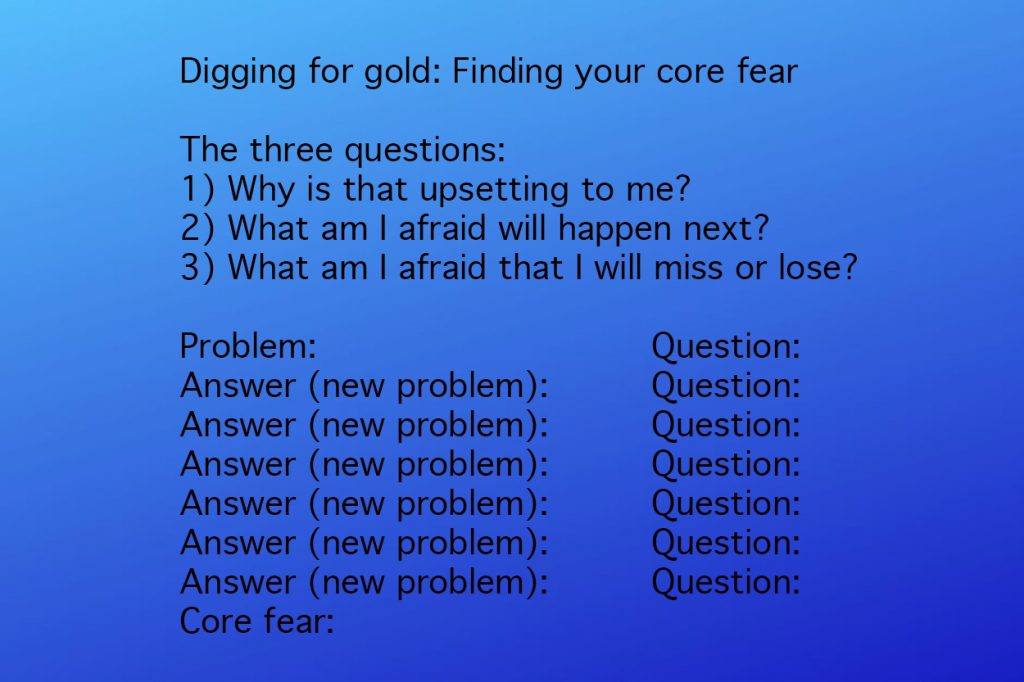

The process of deconstruction starts with an exercise for finding one’s core fear called “Digging for gold.” With this technique, we may quickly and reliably reveal — or we may do so for our clients — the fundamental thought that has been distorting our perception for a lifetime. This exercise is the cornerstone of our model, using a process of deconstruction that goes directly to the root fear underneath all the rest. Here’s how it works:

Begin (or have your clients do so) by writing down a problem on the top left of a page. Any problem will do, because all problems are born, as we shall see, of the same core fear. Make sure your answer is stated as an actual problem and written in a short single phrase, such as “My friend slighted me” or “I can’t pay my bills.” Then write one of the following three questions on the right side of the same line of the page. Choose whichever of these questions seems most fruitful:

1) Why is that upsetting to me?

2) What am I afraid will happen next?

3) What am I afraid that I will miss or lose?

Answer the question with another short single phrase, written on the left side of the line below the first problem. This answer should state a new problem that brings you one level closer to the core fear underlying the original problem. Ask one of the same three questions on the right side of that second line and respond with a short single answer on the third line on the left. Continue with this process until you arrive at what you will clearly recognize as the core fear — a fundamental truth about the real source of the problem with which you started. (See box below for structure of exercise.)

You will know you have arrived at the core fear when you a) keep getting the same answer to the questions and can no longer find a deeper source of fear and b) have an “aha!” experience, a profound recognition that the answer explains something essential at the bedrock of your thinking. Spontaneous connections between the core fear and important events from the past will become apparent, sometimes accompanied by an evocation of powerful emotion and even catharsis.

The real significance of this tool, however, is that as you repeat it with various problems, you will discover that it reveals not only the root of a particular issue or issues but the one true root of literally any problem you can have. This is necessarily so because the core fear is your fundamental interpretation — the overarching assumption — of how the world can be dangerous or threatening. (Note: There are five core fears, or “universal themes of loss,” that capture the basic interpretations of danger that we all make. They are 1) fear of abandonment, 2) loss of identity, 3) loss of meaning, 4) loss of purpose and 5) fear of death, including the fear of sickness and pain.)

Because it is so threatening, so ego-dystonic with our previous state of wholeness, once we land on the core fear interpretation, it makes a powerful imprint on the psyche. We hold on to it as our key to survival — that which will make sense of the danger we’ve encountered and prepare us to be ready for it in the future. It becomes our new understanding of the world, the filter through which we will interpret every experience that presents (or that we can imagine might present) the possibility of danger.

Finding the chief defense

Once we have found our core fear, we must decipher our chief defense, defined as the primary strategy we use to protect ourselves from the core fear. Just as we do with the core fear, we cling desperately to the chief defense, believing it is necessary for survival. But in using this strategy, we unwittingly lock ourselves in to further anxiety because we are reacting to the idea of the core fear as if it were real, as if we are indeed in danger and our protective maneuvers are necessary.

As per the premise mentioned earlier, this is always a distortion of the truth. If we were to examine the real situation, we would at worst find a problem we can deal with rather than the catastrophe our core fear would have us imagine. More often than not, we find the situation we feared holds no threat at all — that the entire idea of danger was made up, a residue of childhood beliefs long held but never challenged.

To find the chief defense then, we simply ask ourselves, “How do I habitually respond to the core fear (or any threat to well-being, since all arise from the core fear)?” We have become so accustomed to our chief defense as our automatic (and only) response to problems that we don’t usually consider alternatives. But as a way to get perspective on our own presumptive response, we can ask ourselves, “How might someone else respond differently in this situation?” or “What is my typical response (overall) when I am challenged or threatened?”

We can also look at many of the major decisions we have made in life and how those decisions were designed to protect us from the core fear of those moments (e.g., the fear of making the wrong decision). There are several other methods for getting insight into one’s chief defense (complete descriptions of these practices can be found in my other publications), but all of them are really different ways of asking, “What is my personality style?” Because it is the core fear and chief defense that set our unique manner (our “personality”) of interpreting and responding to the variety of circumstances life can throw at us.

It bears repeating: The great discovery in this approach is that the core fear-chief defense dynamic gives a sweeping and comprehensive explanation about why we suffer. It not only builds our personality but outlines the entire way we have learned to orient to and interact with life. The extent to which we struggle is the extent to which we have not resolved these fundamental driving forces. Remember, even though they may take care of a problem in the moment, all defenses backfire in the end, reifying and exacerbating the problem they were supposed to protect us from. As we repeat these exercises over and over, we can demonstrate for ourselves that there is, in fact, one core fear and one chief defense operating behind the scenes whenever we are not experiencing the deep fulfillment and sense of wholeness that was our original state.

Once armed with insight into the core fear and chief defense, we are ready to take corrective action. The deconstructing anxiety model has developed several new techniques, including “The Alchemist,” “The Witness” and “The Warrior’s Stance,” for dismantling the chief defense and resolving the core fear. Each of these techniques has been demonstrated clinically to be highly effective in shaking off the hypnotizing effect of fear and waking us up to the truer reality it was hiding. Like pulling back the curtain in The Wizard of Oz, we “do the opposite” of what our chief defense would have us do, thereby exposing the core fear it was hiding. It is this unveiling of the core fear — the secret, primal source of our difficulties — that shows it to be ineffectual. It is but a mouse that roared, casting huge and grotesque shadows on the wall but carrying no real threat.

There isn’t space in this article to go into detail with these techniques, but each is designed to pinpoint the exact moment that our chief defense is applied. By targeting this moment, we may “do the opposite” and expose (rather than defend against) the core fear, revealing its true and distorted nature. But to do so, we must thoroughly move through the fear (at least in imagination) to “disobey” the command of the chief defense. This enables us to pull back from the automatic responses of our personality style, seeing them as arbitrary and encouraging a more effective reply. Combine this with the understanding that there is one core fear and one chief defense responsible for our way of being in the world, and these exercises give us the ability to unravel the entire world of projection that comes from them. It allows us to see through the appearance of danger and shows anxiety to be a lie — an optical illusion if you will — distorted by so much smoke and mirrors.

Case study

Peter (not his real name) was a 48-year-old man who suffered from generalized anxiety disorder. He was especially anxious about the idea of physical sickness and pain and of emotional rejection, and he struggled with the limitations of being human. It was evident from our first meeting that he had been raised by an overprotective mother who had shielded him too well from the exigencies of life.

When Peter was 9 months old, he became very sick and was hospitalized. In addition to the physical pain he experienced, he must have been terrified about being separated from his mother in a strange, cold environment with strange people poking and prodding him. When he returned to the security of his home, he regressed, clinging tightly to his mother and showing behaviors he had previously grown out of. He stayed young and dependent throughout his childhood.

At age 14, Peter began a tumultuous adolescence, experiencing his hormonal changes as an overwhelming challenge to his identity. His first response was to try to cling to his parents for comfort, but for the first time since his hospital experience, they were not able to calm him. This increased his anxiety all the more and solidified his core fear, which he described to me as being “exposed to the elements and to death, without any real security.” His response at age 14 was to make a powerful resolve that if his parents could not protect him, then he would find a way to gain a sense of control on his own.

As Peter grew older, this translated into various behaviors (what the deconstructing anxiety model calls “secondary defenses”) in which he would be “the best” at whatever he pursued: the best student, the best athlete, the most popular kid at school and so on. These behaviors represented his strategy for trying to reclaim the sense of safety and security he once knew. Putting these secondary defenses together, he described his chief defense (the umbrella description overarching them all) as “I have to be special.”

This response style would become Peter’s personality, following him throughout his life. Although it created a good deal of ambition in Peter — a drive to evoke his fullest potential — it was clear this drive was compelled by fear, a somewhat frantic need to be special. Therefore, it belied his anxiety of accepting the necessary limits of the human condition in a way that could have led to real growth and transformation. Instead, Peter felt stuck in a self-repeating loop that was the cause of his generalized anxiety — every time he became anxious, he would try in earnest to “beat” the problem, looking for the next way to prove his worth and “specialness.” Like any defense, this would provide momentary relief but then backfire, inevitably creating more anxiety when Peter was confronted with some new vulnerability, thus beginning the process all over again.

In our work together, Peter quickly uncovered his core fear and chief defense and developed a healthy appreciation for the futility of the strategy they proposed for well-being. With these insights in hand, we began the exercises for correction in the deconstructing anxiety program. In each, we gently but firmly confronted Peter’s chief defense of being special and practiced “doing the opposite.”

These exercises targeted the exact instant when Peter would defend against his core fear and provided a structure for safely and completely moving through the defense. In doing so, Peter could see the impulse to exercise his chief defense as an arbitrary choice. This allowed him to live through (in imagination) the full force of his core fear, coming to a deep acceptance of that from which he had been running his entire life. Sticking with this process, Peter’s chief defense “dissolved” (his word), no longer able to convince him that there was something threatening to defend against. He had faced his fear of not being special and relaxed into the fact that he was “ordinary, just like everyone else.” However, he no longer interpreted this as a source of pain or disappointment.

Quite the contrary, with a great look of surprise on his face, he stated, “It’s so freeing to be ordinary. I see how my whole life I’ve been working so hard to prove I’m special. All that did was keep me anxious, always worrying about failing at my goal. How ironic. I wanted to be special so I could get love and security. But I was the one keeping myself apart from that, thinking I had to be more than I was in order to earn that love.”

This is not an isolated example. Every time we face the core fear without the interference of the chief defense, we will find that the core fear is not “real” in the sense we had thought. This is the promise of deconstructing anxiety: When we clearly see the hidden forces that have been driving our lives, we can take those therapeutic actions that will set us free. This means moving through the chief defense that was hiding our core fear, exposing ourselves gently but firmly to the fear, and discovering that our core fear does not have the power to carry out its threat as promised. Even if a problem remains to be managed, it does not represent a true call for fear once the assumptions that made it frightening are stripped away.

What’s more, we find that the vast majority of our fears and anxieties are completely made up, projections built on ideas learned long ago that have no bearing on our circumstances today. This is the great key to freedom, a prescription for how to live our lives from a new premise — one based not on fear and anxiety but on the ability to consciously choose our way according to our highest ideals and deepest fulfillments.

****

Todd Pressman is a licensed psychologist, author and speaker specializing in the treatment of anxiety and the pursuit of fulfillment. His most recent book, Deconstructing Anxiety: The Journey From Fear to Fulfillment, was published this past summer (see toddpressman.com for more information). Contact him at pressmanseminars@gmail.com.

Todd Pressman is a licensed psychologist, author and speaker specializing in the treatment of anxiety and the pursuit of fulfillment. His most recent book, Deconstructing Anxiety: The Journey From Fear to Fulfillment, was published this past summer (see toddpressman.com for more information). Contact him at pressmanseminars@gmail.com.

Knowledge Share articles are developed from sessions presented at American Counseling Association conference.

Letters to the editor: ct@counseling.org

**** Opinions expressed and statements made in articles appearing on CT Online should not be assumed to represent the opinions of the editors or policies of the American Counseling Association.

- Anxiety Disorders

- Assessment, Diagnosis & Treatment

- Counselors

Search CT Articles

Filter CT Articles

Current Issue

Sign Up for Updates

Keep up to date on the latest in counseling practice. Sign up to receive email updates from Counseling Today.