Untangling trauma and grief after loss

By Lindsey Phillips

May 2021

Death, loss and grief are natural parts of life. But when death arrives suddenly and unexpectedly, such as with suicide or a car accident, the overlap of the traumatic experience and the grief of the loss can overwhelm us.

Glenda Dickonson, a licensed clinical professional counselor in private practice in Maryland, describes traumatic grief as “a sense-losing event — a free fall into a chasm of despair.” As she explains, the experience of having their everyday lives ripped apart by a sudden and unexpected death can cause people to go into a steep decline. “They are down there swirling,” she says, “experiencing all the issues that are part of grief — shock, disbelief, bewilderment.”

In some cases, people get stuck in their grief and can’t seem to find a way forward. And in certain instances — such as when someone loses their child — individuals may not even want to get out of that state because, for them, it creates a sense of leaving their loved one behind and moving on, adds Dickonson, a member of the American Counseling Association.

Elyssa Rookey, a licensed professional counselor (LPC) at New Moon Counseling in Charleston, South Carolina, worked with a client who had experienced two traumatic losses. When the client was 15, his stepfather died from suicide, and when the client was 20, his mother died on impact in a car accident. After the death of his mother, the client started having nightmares and became anxious about the possibility of losing other loved ones in his life.

Rookey noticed that the client used “I” statements frequently in sessions: “I should have done more to help them. I shouldn’t have said that before she left.” The client blamed himself for their deaths and thought that he was cursed, says Rookey, who specializes in treating trauma, grief and traumatic grief.

His mother’s death also triggered the client’s feelings of abandonment in connection with his biological father, who had left him when he was a child. At times, the client wanted to avoid others and be alone, but that subsequently increased his feelings of isolation and fear of additional loss. He also hosted feelings of anger about having to “grow up” and assume adult responsibilities, such as paying a mortgage and keeping a piece of property maintained, before he was ready. In many ways, Rookey says, he was “stuck” in the trauma and avoiding the feelings of grief and loss.

Identifying traumatic grief

Not every sudden or catastrophic loss results in traumatic grief. Some people experience uncomplicated bereavement. But others may show signs of both trauma and grief. They might avoid talking about the person they lost altogether, or they might become fixated on the way their loved one died.

Because of the trauma embedded within the grief, it can be challenging to differentiate between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), grief and traumatic grief. “PTSD is about fear, and grief is about loss. Traumatic grief will have both, and it includes a sense of powerlessness,” Dickonson explains. “A person who is experiencing traumatic grief becomes a victim — a victim of the trauma in addition to the loss. … They will assume those qualities of experiencing trauma even while grieving the loss.” She finds that people who have traumatic grief tend to talk about experiencing physical pains, have trouble sleeping and are anxious.

People experiencing traumatic grief could have distressing thoughts or dreams, hyperarousal or anhedonia/numbness, says Nichole Oliver, an LPC in private practice at Integrative NeuroCounseling in Chesterfield, Missouri. She notes that some of the symptoms can be confused with other mental health issues. For example, a person going through traumatic grief may have a loss of appetite and trouble sleeping (which can resemble signs of depression) or have great difficulty focusing (which can look like a sign of attention-deficit disorder).

On its website, the Trauma Survivors Network lists common symptoms of traumatic grief, which include:

- Being preoccupied with the deceased

- Experiencing pain in the same area as the deceased

- Having upsetting memories

- Feeling that life is empty

- Longing for the person

- Hearing the voice of the person who died or “seeing” the person

- Being drawn to places and things associated with the deceased

- Experiencing disbelief or anger about the death

- Thinking it is unfair to live when this person died

- Feeling stunned or dazed

- Being envious of others

- Feeling lonely most of the time

- Having difficulty caring about or trusting others

Rookey, who also works for the South Carolina Department of Mental Health in partnership with the Charleston County Sheriff’s Office, always screens for trauma because clients may have underlying issues that affect or complicate their grief. When working as a counselor in Miami, she noticed that some adolescents who were court referred for their substance use had also experienced traumatic loss (having a friend who was shot and killed, for example). In these cases, counseling sessions focused on grief, PTSD and anxiety in addition to the issue of substance use, she notes.

Rookey first meets with clients to get a better sense of their story. These conversations often lead her to ask questions such as “Have you ever felt this sense of loss or fear in the past?” The questioning helps uncover underlying issues that may be affecting the person’s ability to grieve in a healthy way, she explains. For example, a client might reveal that the way they’re currently feeling reminds them of how lost they felt after their parents’ divorce. This may lead to the discovery that the client never fully dealt with that loss at the time, and that is now affecting how they are processing this new loss.

A new layer of loss

“COVID-19 brought a brand-new dynamic to grief,” says Dickonson, who specializes in treating trauma, bereavement, traumatic grief and mood disorders. “People have lost jobs, relationships, businesses and homes. … There is an endless sense of loss that keeps coming on.”

The pandemic has also added a layer of trauma to expected grief because it has restricted the ways that people are able to mourn death. Rookey, who is also an LPC in Florida, had a client whose husband died not long before the COVID-19 virus reached the United States. After the husband’s death, the client moved from Florida to South Carolina, where her husband was from, because he had always wanted their children to live there. A few months later, the client’s aunt in Puerto Rico died from natural causes, but because of quarantine restrictions, she was unable to travel to attend the funeral. All of these circumstances left the client feeling helpless, frustrated and isolated, Rookey says.

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely curtailed people being able to grieve communally, which can make even anticipated deaths more traumatic, Rookey notes.

“Losing a loved one to COVID-19 could definitely complicate the grieving process when people are unable to say goodbye or to be with their loved one when they pass,” says Tamra Hughes, an LPC in Centennial, Colorado. “Those experiences can torment a person who is trying to come to terms with the loss.”

“And COVID-19 is front and center in all we see and do right now. So, there is a constant reminder of the circumstances of the loved one’s death,” she continues. “These cues can all act as triggers for the client, eliciting negative emotions, physiological reactions and trauma responses.”

Grief is personal

Everyone grieves differently, so identifying traumatic grief in clients is not always a straightforward matter. Hughes, an ACA member who specializes in grief, traumatic grief, trauma, complex trauma and anxiety, says no two cases are the same in grief work. She approaches her work through the lens of the adaptive information processing model of eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. Among the areas she considers are the client’s level of stability in their life, their attachment style and their mental model of the world. These factors affect the way they manage adversity and trauma, Hughes explains.

Working as a counselor at a funeral home helped Oliver, an ACA member who specializes in PTSD and grief, understand and appreciate how people’s social and cultural factors (such as personality, spirituality and race/ethnicity) affect how they approach loss and mourning. For example, under some religious beliefs, shame is attached to suicide, whereas others may celebrate it as a brave act. And while some people consider crying a weakness, certain cultures incorporate wailing into their funeral ceremonies.

Hughes, the owner and therapist at Greenwood Counseling Center, knows that some clinicians are afraid to ask clients about their spiritual beliefs regarding death. She encourages counselors to ask difficult questions such as “What do you think happens to people after they die?” Otherwise, “it becomes the elephant in the room,” she says. “It’s not about putting your own religious or spiritual beliefs on the client. It’s about understanding the [client’s] context … because then you can work within that framework to help them through the grief.”

Legal proceedings connected to homicides can further complicate a person’s experience with grief. Sometimes people assume that the best way to process their grief and heal is through seeking legal justice, Rookey says. But often, their grieving doesn’t really begin until after they separate the legal aspect from their own grief and trauma, she observes.

Oliver uses individual clients’ unique life experiences to tailor her psychoeducation efforts and counseling techniques. For example, she may explain trauma symptoms to someone who works in information technology by comparing their body to a web browser that has too many open tabs. This visualization helps the client understand why their body and emotions are overloaded. Then she’ll ask the client to pick which two or three tabs they want to prioritize and work on that session.

Oliver also has clients put together a playlist of songs that express their current mood and their feelings of mourning, which may be difficult for them to convey verbally. In session, clients can use these songs to explain the way they are processing their grief in that moment. That helps regulate the limbic system, which is the part of the brain involved in behavioral and emotional responses, she says. Oliver also keeps a three-ring binder of images — such as a person bent over in shame or a person torn in half between their heart and brain — in her office. Sometimes she asks clients to select an image that resonates with them as a way to jump-start their conversation.

Unspoken words

People may come in for counseling immediately after a sudden loss, or they may wait weeks or even months before seeking help. If the counselor does begin working with the client soon after the loss, their main goal during those first two or three weeks of therapy should be to “hear” the client’s loss and validate their feelings, Hughes says. Counselors could offer some guidance for coping and self-care, but she cautions against making suggestions about how to “heal” because that can sound dismissive.

Dickonson finds “sacred silence” — silently sitting and being present with a client — a useful tool when working with traumatic grief. “We have to develop the capacity to sit with our client’s anguish, to stay fully present but not be intrusive, and to speak but also know how to be quiet and fully connect. We don’t have to break the silence. … Sometimes that’s what they need. They just need us to be there with them and show them that we care,” she says.

Dickonson also keeps a tissue box within reach of clients in case they want it, but she does not offer them a tissue if they start crying. “Tears are very cathartic, and if I give you a tissue, it can [insinuate] that it’s time to stop crying,” she explains.

Hughes eventually provides clients with a space to voice unspoken words — what they would have liked to say to their loved one and what they think their loved one would have said to them. “There’s something about articulating it and speaking those words [out loud] … that contributes to helping the brain reconcile some aspects of [the grief],” she says. It also provides clients with an opportunity to get closure on something that feels so abrupt and unfinished, she adds.

One technique that Dickonson uses with some of her clients as they begin emerging from their grief and have started their journey to posttraumatic growth is to assume the voice of the deceased and then write or record how they believe their loved one would comfort them. As a prompt, she asks clients, “What would your beloved say to you if they were here right now?”

As clients share their interpretation of their loved ones’ words, Dickonson watches the way their face changes at certain parts and then asks, “How did you feel when you heard what your loved one might have said to you?” She finds this exercise often leads to productive discussions and helps clients give voice to things they might feel guilty for saying themselves.

Processing the trauma

When Hughes helps clients process life challenges, including traumatic grief, she addresses their trauma through EMDR. Hughes is an EMDR therapy trainer, the owner of EMDR Center of the Rockies, a member of the board of directors for the EMDR International Association (EMDRIA) and an EMDRIA-approved consultant. “EMDR helps the brain to organize information in a way that is more adaptive. In the case of traumatic grief, it can help foster healing and closure in the grief process,” she explains.

If conflict existed in the relationship with the person who died, clients may need to work through challenges that they had or feelings of guilt or shame that can be present following the loss, Hughes adds.

A traumatic loss can also trigger a past trauma, which might be the underlying reason for the client’s current complicated grief response, Oliver says. She once worked with a man whose mother had just died. Although their relationship had been strong at the time of her death, the client’s mother had been abusive when he was a child. Her death triggered this past childhood trauma, causing the client to feel not only grief over her loss but also anger for the past abuse and guilt about the relief he felt for no longer having to care for her. The client was afraid to admit these complex feelings to Oliver because he was ashamed for feeling resentment, anger and relief when he thought he should be feeling only grief. The client’s cognitive dissonance disrupted his ability to grieve in a healthy way and further anchored him in a complicated grief response, Oliver notes. She validated his feelings and reminded him that expressing the full range of his emotions didn’t mean that he was attacking his mother’s memory.

Rookey has used exposure therapy to help clients process unresolved trauma around losses that they experienced firsthand. But she cautions clinicians not to use the approach if they think it could be triggering for a client, especially if the client doesn’t have a good support system.

Rookey used the approach with a woman who became triggered by the sound of sirens after she watched her partner die from a traumatic accident. While the woman was sleeping, her partner went outside to smoke, and he was shot after being caught in the middle of a botched burglary. By the time the woman woke up and realized what was happening, her partner had crawled inside the kitchen and was slowly dying. She called 911 and held him while she waited for the ambulance.

It wasn’t just the grief of loss that was traumatic for the client, Rookey explains. It was the trauma of repeatedly asking herself, “Why didn’t I do something to help him?”

The client began to operate in survival mode and avoided thinking about her loss. But sirens became a trigger for her. When she heard them, she would run to a bathroom and cry. So, Rookey decided to use in vivo exposure to help the client retrain her body and mind to get to a healthy state again.

First, Rookey asked the client, who worked near a hospital, to step outside whenever she heard an ambulance and listen to the sirens while engaging in calming activities such as deep breathing. After the ambulance passed, the client would repeat positive affirmations (e.g., “It wasn’t that bad”). This slowly exposed the client to the trigger in a safe way. After the client was comfortable hearing the sirens outside her work, Rookey had the client record herself recounting the traumatic incident as if she were reliving it, and she replayed this recording every day. “It’s a way to show your body you can get distressed, can get triggered, can be fearful, but you will be OK,” Rookey says.

In session, Rookey asked the client what parts of the story affected her most. This questioning helped Rookey discover that the client’s guilt over not preventing her partner’s death was what was holding her back from fully grieving and moving forward. They worked together to reframe the event to help the client realize she was not responsible for the death: Her partner always stayed up late and smoked a cigarette before bed. She had called for help. There was nothing else she could have done.

Creating new meanings

What makes a loss traumatic is not only the way the person died but also the meaning attached to the death, Oliver says. She worked with a woman who had developed an irrational thought attached to her son’s traumatic death. The son had been struggling with a drug addiction for a decade, but the night before he died from suicide, they had had a fight and the mother had said some unkind things. She blamed herself for his death.

“Her core belief [that she was responsible for her son’s death] kept her anchored to the pain of the grief, so we couldn’t process the grief until we relinquished that belief,” Oliver says.

To begin the process of untangling the client’s negative belief from her grief, Oliver presented another contributing factor to the son’s death. She told the client, “Numerous research studies reveal complex neurobiological changes in the brains of individuals who have completed suicide. Postmortem autopsies reveal that these individuals have 1,000 times the cortisol in the brain, and other systems such as the HPA [hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal] axis, receptors and neurotransmitters are not functioning normally. That means they do not have access to the prefrontal cortex, the reasoning part of the mind.”

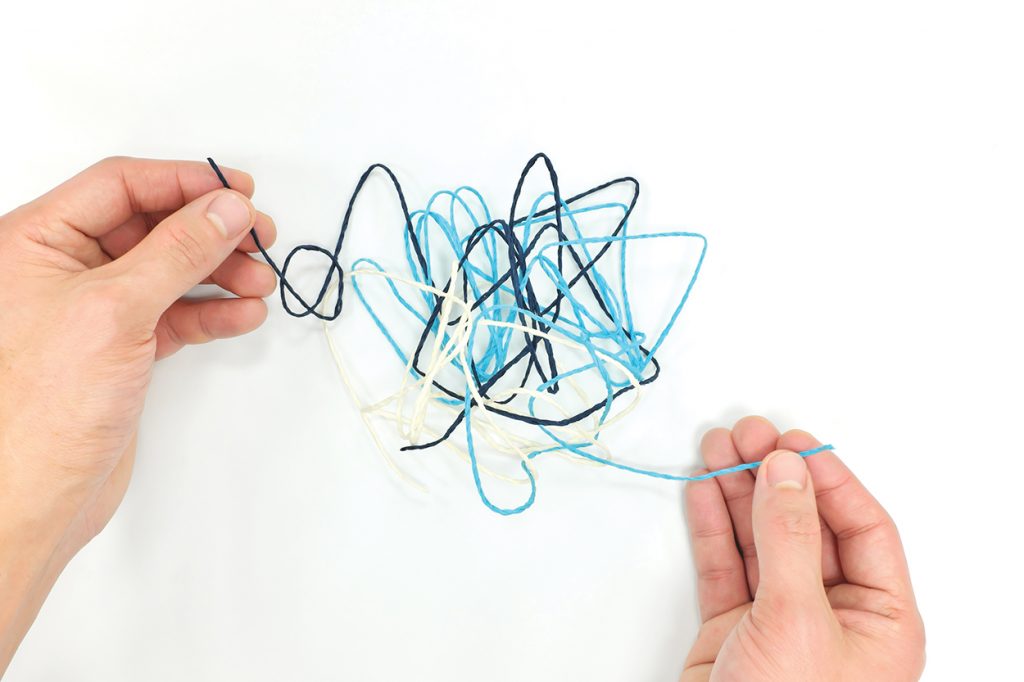

That information comforted the client. When addressing traumatic grief, it’s often about planting seeds of hope and disentangling the fragmented pieces in people’s minds, Oliver says.

Oliver continued to help the client find and connect the fragmented pieces through memory reconsolidation, which is the brain’s innate process for transforming short-term memories into more stable, long-lasting ones. Oliver had the client recall the memory of her son’s death, and then they created mismatched experiences in the brain by pairing the client’s belief that she was responsible for her son’s death with the contradictory information that she had supported him through rehab and that he had attempted suicide previously.

Recalling this information caused a clash with the client’s cognitive distortion that the son’s death was all her fault, Oliver explains. The process helped the client integrate more pieces of the puzzle until she had a clearer picture of the event and was able to get “unstuck” from the negative thought. As a result, the emotionally charged memory (the client’s self-blame) moved from the amygdala to the hippocampus, reducing the trauma response by creating new learning (the realization that her son’s death was not her fault), Oliver adds.

Finding a way forward

After mitigating the trauma of their loss, clients are ready to take a step forward. “With traumatic grief, it’s about making meaning of the death and who they are now,” Rookey says. “They were on one course … and it got skewed, and now they’re on a parallel path.” After processing through the trauma and grief of the loss, she has clients visualize themselves moving forward on the different path. The exercise encourages them to think about their future and gives them some meaning as they start down this new path, she says.

Hughes believes the goal is “to get to a place where the grief is replaced by increases in the positive memories of the person and the essence of who they were.” People will still feel sadness about the loss, but this feeling should be more manageable and is coupled with gratitude for the time shared with the loved one, she explains.

With counseling and support, clients can emerge from the “chasm of despair” — the steep decline they fall into after the traumatic loss — and begin to transform their pain into something positive and potentially powerful, Dickonson says. That might include being more involved with their families, developing a greater appreciation for life or even embracing new opportunities that emanate directly from the traumatic event. “They still feel the sadness,” Dickonson says, “but they are ready to move forward.”

This is when counselors could encourage — but not push — clients to continue their transformation process from the sense-losing free fall to a sense-remaking journey, Dickonson advises. Counselors should also be mindful that when clients come out of the grief abyss, they may replace their grief with another unhealthy coping behavior, she cautions. So, counselors have to continue to support clients as they start this journey forward.

Rookey and her client who lost his stepfather and mother all before he turned 21 had to address his negative beliefs about his responsibility in their deaths before he could find a way to move forward and grieve in a healthy way. By the end, the young man’s guilt and anger had lessened. He sold his mother’s home, bought a truck and set up autopay for his bills. These were small steps toward him carving out his new identity and moving forward on his parallel path.