The impact of legalized marijuana on professional counseling

By Bethany Bray

March 2022

In 1996, California voters passed Proposition 215, making the Golden State the first in the U.S. to legalize the use of medical marijuana.

Two decades later, the medical use of cannabis is legal in 37 states, Washington, D.C., and the territories of Guam, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Additionally, 18 states, Washington, D.C., and two territories have enacted legislation to regulate cannabis for nonmedical (i.e., recreational) uses, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Just three states — Kansas, Nebraska and Idaho — do not allow public access to cannabis in any form, medical or otherwise.

In states where cannabis use has been legalized, many medical and mental health practitioners have found it necessary to shift their mindset — from viewing marijuana as an illegal substance to something that medical doctors can condone or even recommend and that potentially has benefits for a range of conditions, including chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“When it was first becoming legalized, it was a bit of a panic for the [addictions] treatment community around ‘How are we going to deal with this?’ What has evolved is that now, it’s viewed in a similar way as alcohol is: There is a continuum of users, [and] it can be abused but also used socially or occasionally,” says Adrianne Trogden, a licensed professional counselor and supervisor (LPC-S) and licensed addiction counselor (LAC) with a private practice in New Orleans. “It’s a hard transition for treatment providers to go from thinking of it as an illegal street drug to being dispensed as a medicinal medication. … In treatment facilities, you see the worst of the worst — those whose lives have been ruined by substance. It’s easy to see the ugly side of addiction and naturally be leery of [marijuana] being used for medicinal use. That mindset is hard to shift.”

Legalization has also meant that professional counselors cannot keep their heads in the sand about this issue, regardless of how they feel personally about the use of marijuana, says Paula Britton, a licensed professional clinical counselor and supervisor with a private practice in Cleveland. Practitioners need to be comfortable broaching the subject of how and why a client uses marijuana, and they should be familiar with the pros and cons of the substance as it relates to adult mental health and wellness. In addition, they should understand the nuances of cannabis regulation in their state.

At the same time, counselors must know how to assess clients for cannabis use disorder and listen for indicators that an individual may be drug seeking, Britton says.

Talking about clients’ marijuana use “gets tricky,” admits Britton, who is licensed as both a counselor and a psychologist. “Because of that, many counselors don’t want to get involved or learn about it. But I don’t know if we’re going to have that option in the years to come” as it becomes increasingly legalized. “We have to be aware that this is going on and that [marijuana use] is helpful for some people,” she continues. “We have to acknowledge that our clients are using it, or wanting to use it, for medical or recreational purposes and [consider] what … that mean[s] for us in counseling.”

Mixed messages

Cannabis is classified as a Schedule 1 substance under the Controlled Substances Act, which makes its distribution a federal offense. This puts marijuana alongside heroin, ecstasy, LSD and other substances that are “defined as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse,” according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

This sends a confusing and mixed message, both to the public and to health professionals, given that marijuana may be legal and OK to use at the state level yet illegal federally, Britton says. In addition, the complicated regulatory scheme has impeded much-needed research on the effects marijuana can have on a range of conditions when used in a controlled, medically sanctioned way.

In the meantime, counselors must rely on the limited research that has been done by other disciplines or by researchers outside of the country. The few studies that have been done have yielded mixed results on marijuana’s efficacy for mental health diagnoses, particularly anxiety and depression, Britton notes.

“There’s just so much we don’t know,” says Britton, a professor of clinical mental health counseling at John Carroll University. “If we [counselors] are going to be evidence based, it’s hard to have an informed decision about what you think without that [research] behind you.”

One example of the mixed messaging surrounding cannabis use involves the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The VA has done studies that show medical marijuana can help individuals with PTSD, yet it will not endorse its use for VA patients because of the federal law, Britton notes.

The American Psychiatric Association issued a position statement in 2019 saying that it would not endorse the use of medical cannabis for the treatment of PTSD “because of the lack of any credible studies demonstrating [its] clinical effectiveness.”

Aaron Norton, a licensed mental health counselor, licensed marriage and family therapist and certified rehabilitation counselor with a private practice in Largo, Florida, suggests that the mixed data regarding marijuana use allows people who argue either for or against its legalization to cherry-pick studies that support their view. Some people, for example, have cited reports linking the legalization of medicinal cannabis with lower opioid overdose mortality rates as evidence that medical marijuana is the answer to ending America’s opioid epidemic.

“What I am concerned about is the touting of medical cannabis as the cure-all magical wonder drug,” says Norton, who has written and presented on legalized marijuana’s impact on the counseling profession. “There is contradictory evidence out there … [and] overall there’s very little evidence that medical marijuana helps many of the things that we think it does. I’m concerned about the claims that are made and [the] use of it in mental health treatment.”

It is well-known, however, that marijuana use can have a negative impact on child and adolescent brain development and has also been tied to lung problems (when used in inhaled forms) and other challenges later in life, Britton says. She advises counselors to also be mindful that marijuana use can affect the efficacy of psychotropic medications such as antidepressants that are commonly used by clients.

Even when used legally, marijuana can still have adverse effects on clients’ employment, particularly if they work for the federal government or in fields that require regular drug testing. Marijuana stays in the human body and can show up on drug tests weeks after a person uses it, notes Britton, who co-authored a recent Journal of Counselor Practice article on Ohio mental health professionals’ attitudes, knowledge and experience regarding medical marijuana.

This aspect of marijuana use also has implications for counselors who work in the field of substance use because it can be difficult to determine an individual’s length of abstinence, says Trogden, an assistant professor in the counseling department at the University of the Cumberlands.

Dosing concerns

Dosing is another potential area of confusion related to legalized marijuana for individual users and health professionals.

Norton says that in Florida, it is mostly left up to the individual to purchase and use whatever dose they believe is best — a situation he labels a “free-for-all.” Physicians in Florida do not prescribe specific doses to patients who are granted a medical marijuana card because it remains illegal federally, he explains.

Similarly, Britton points out that employees at marijuana dispensaries in Ohio are not doctors and will often sell customers whatever dosing amount they request. Determining the correct cannabis dosing is complicated because the “optimal dose” will be different for every person, she says. The same amount of substance will affect people differently depending on whether it is inhaled or eaten, such as in gummy candy or baked goods.

Matthew McClain, a school counselor in Fort Morgan, a small town in northeast Colorado, notes that dosing is a concern for youth because they often won’t read or adhere to the instructions or labeling for items that have come from a cannabis dispensary. For example, a teenager may open a marijuana brownie or piece of cake and eat the entire thing without pausing to read or acknowledge that it may be equal to two or three servings. “That can be pretty significant for the [body] systems of a teen,” says McClain, the executive director of the Colorado School Counselor Association (CSCA).

School counselors in Colorado are finding that youth (mostly in middle or high school settings) have adopted more casual attitudes about marijuana since its legalization in the state, McClain notes. In recent years, he says, school counselors’ awareness and concerns have shifted from students smoking marijuana to their consumption of it via vaping or edibles, both of which feature a high concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the component in marijuana that produces a high. These methods allow students to consume the substance in a more clandestine way than smoking does, including during the school day. Edibles such as candy or gummy bears also make exposure and consumption of marijuana more familiar and less foreboding to youth.

One way to counteract this issue is to train teachers and noncounseling school staff in mental health first aid, McClain says. This can better prepare school staff members to notice behavior changes and other indicators that a student might benefit from talking with a school counselor — about marijuana use or anything else, McClain says. CSCA also offers regular trainings and continuing education programming to its members on marijuana use and its effects in school settings, he adds.

“This just adds another layer of complexity to the job, one other thing that can be going on” with students, McClain says. “We [at CSCA] have made sure that we’ve provided [educational] opportunities by seeking out experts and people who are well-versed to provide information and training, and other states are in a similar situation. We may want to stick our heads in the sand, but at the same time, if we’re dealing with the day-to-day lives of our kids, we want to make sure we can provide help and support.”

Use as instructed?

Norton says that in his experience, only a small fraction of his clients who have medical marijuana cards use the substance for medical reasons. He believes the majority obtained a medical marijuana card so they could use it recreationally, which remains illegal in Florida, or because they have cannabis use disorder.

When asked, many of these clients are unable to tell Norton why they have a medical marijuana card, or they name conditions — such as headaches, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and trouble sleeping — that aren’t listed on the state statute that allows for the use of medical marijuana. The only mental health diagnosis mentioned in Florida’s statute is PTSD, Norton says. However, there is language in the law that allows medical marijuana to be prescribed for “similar” conditions to those listed in the statute, which gives physicians flexibility. Norton says he has never heard of a client who has been turned down for a medical marijuana card.

“Even clients who perceive they are using it medically … judge its efficacy by [not only] if they feel better but also [if they] feel high or euphoric — and that’s not the point of medicine,” says Norton, the executive director of the National Board of Forensic Evaluators and an adjunct instructor at the University of South Florida’s rehabilitation and mental health counseling program. “People are using cannabis to feel better in the moment — sleep better, lessen anxiety, etc. — but at the expense of addressing their core problems, which are thoughts and behaviors. They’re missing the opportunity for recovery from their behaviors.”

Trogden agrees, saying, “The challenge, just as with any other medication, is that you really need therapy and counseling services to gain insights and awareness [about a presenting issue] along with taking the medication.” She adds that in her experience, medical marijuana has benefited clients who have depression or other mood disorders, trouble sleeping, anxiety, racing thoughts or a history of trauma. But Trogden also notes that in addition to its potential benefits, marijuana use can cause paranoia or lead individuals to use it as a “crutch” to cope with pain and other difficult feelings.

Britton has done research on medical marijuana and counseled clients who use it. She says the substance can be tied to symptom relief or otherwise benefit individuals who have chronic pain, sleeping difficulties, autism spectrum disorders, anxiety and hyperarousal, nausea (such as in those undergoing chemotherapy treatment for cancer) and a range of other issues. At the same time, she says that more research is needed.

In Britton’s experience, medical marijuana has helped some of her clients, while others did not reap any benefit — or even had negative outcomes — from its use. “And that’s consistent with the literature,” she notes. “Not everyone benefits. It’s not a miracle cure. But just like with antidepressants [and other psychotropic medications], it can soften a client’s symptoms … [so they can] do the therapeutic work. But they still need behavioral intervention.”

Now that marijuana is legal in most states, the counselors interviewed for this article agree that clinicians should include specific, detailed questions about its use during the client intake process. Asking clients how often and why they use marijuana can help practitioners better understand the context of their use and assess for dependence or cannabis use disorder.

Cannabis use disorder is characterized by behaviors that indicate that a person cannot stop using the substance even though it is causing the person social or health problems, such as overusing or craving marijuana or driving while impaired. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, individuals who use cannabis frequently or began using it in adolescence are at greater risk of developing this disorder.

Practitioners should embed questions into assessment about how much and how often clients use marijuana, similar to the way they would ask about clients’ consumption of alcohol, suggests Trogden, who teaches in an addiction counseling training program for the state of Louisiana and is the chief operating officer of a behavioral health organization in New Orleans.

“We should be assessing for a variety of things. It’s helpful to understand the whole person and get a holistic understanding of what’s going on. Substances would be a part of asking about medication, whether it’s blood pressure [medication], mental health medication or marijuana,” Trogden says. “It’s important to call it out specifically, [asking] ‘Do you use marijuana?’ If you just ask, ‘Do you use drugs?’ they’ll probably say ‘no.’”

Trogden says multiple clients have mentioned to her in later counseling sessions that they smoke marijuana after initially answering “no” to generalized substance use questions at assessment. As a result, she’s learned to ask specifically about marijuana in assessment because some clients do not consider it to be a drug or on the same level as illegal substances.

Britton suggests that counselors take a nonjudgmental, curious and respectful approach to marijuana assessment with clients. “If a client senses that you are going to judge them — on any topic — they’re probably not going to tell you,” she says. “Start thinking differently about how you ask [and] how you put it on intake forms. Get outside of judgment.”

When clients ask

Clinicians in states where marijuana is legalized may have clients ask whether it could help them with symptoms related to their presenting concern or mental illness. Counselors cannot prescribe medication, however, and making a recommendation or giving guidance on marijuana use — or any other kind of health regimen — goes beyond a counselor’s scope of practice, says Emily St. Amant, counseling resources and continuing education specialist for the American Counseling Association. She recommends that counselors refer to the 2014 ACA Code of Ethics, particularly Standard C.2.a.

St. Amant, a licensed professional counselor with a mental health services provider designation in Tennessee, urges counselors to respond to client questions about legalized marijuana use with a nonjudgmental attitude and a recommendation to speak with a licensed psychiatric medical provider about the topic.

“I would also provide education about why I’m making that recommendation: my own scope of practice [and how a prescriber is qualified] to discuss risks and benefits, side effects, drug interactions, etc.,” says St. Amant, whose background is in substance use counseling. “As a counselor, I need to ensure I’m staying within my scope of practice or what I’m personally licensed to do. We open ourselves up for liability and ethical violations when we drift out of our lane and into the lane of other areas of expertise. We also open ourselves up for potentially harming our clients if we impose our own values or ideas on them. That takes away their autonomy, can damage the therapeutic relationship and creates a power imbalance.”

Rather than offering advice to clients regarding legal marijuana use, counselors should focus on strengthening clients’ personal autonomy and decision-making skills, St. Amant emphasizes. Ultimately, it is the client, not the counselor, who must make and live with the decision to use (or not use) marijuana, medicinally or recreationally.

“That doesn’t mean we leave them hanging and avoid helping in some way. That would be risking invalidating the client’s concern and a missed opportunity to be supportive,” St. Amant says. “We can help our clients by providing education, teaching problem-solving skills, eliciting their decision-making process, validating their concerns and promoting their empowerment and autonomy. … Even for us experienced counselors, it’s vital to ensure we are staying true to the fundamentals of client-centered principles. Those that are particularly relevant here include the fact that clients are the experts in their own lives and that we genuinely trust that they can decide what’s best for them.”

Decision-making

Talking about a client’s marijuana use in counseling sessions will have a very different dynamic depending on whether the individual is voluntarily pursuing treatment or has been mandated to complete therapy, often as the outcome of a court case.

In the second scenario, practitioners must remember — and explain to the client — that their work goes beyond the needs of the individual client, Norton says. The client may want to get their driver’s license returned after a DUI violation, for example, and this is contingent on completing a regimen of counseling sessions.

“The counselor is responsible not only for the safety of their client but [also for] the safety of the public,” Norton says. “You have to address the issue [of their marijuana use]. You can’t ethically clear them if they’re just as unsafe now [at the conclusion of therapy] as when they first came to you. Counselors now have more than one stakeholder in what you do.”

Norton is a counselor supervisor, and his interns often work with clients who are mandated to complete counseling after a DUI or whose children have been removed from their care by child protective services because of their marijuana use and related behaviors. Norton also sees similar scenarios in the work he does as a substance use and DUI evaluator for the court system in Florida.

It is common for clients to try to skirt the sobriety requirements in mandated treatment situations by obtaining a medical marijuana card, according to Norton. This scenario puts the counselor in a no-win situation because the client has a way to legally obtain marijuana and continue their behaviors, he says. Addressing the root of the problem that brought the client into counseling becomes exponentially harder because the counselor is not a medical professional and cannot advise the client to stop a medically prescribed treatment, Norton points out.

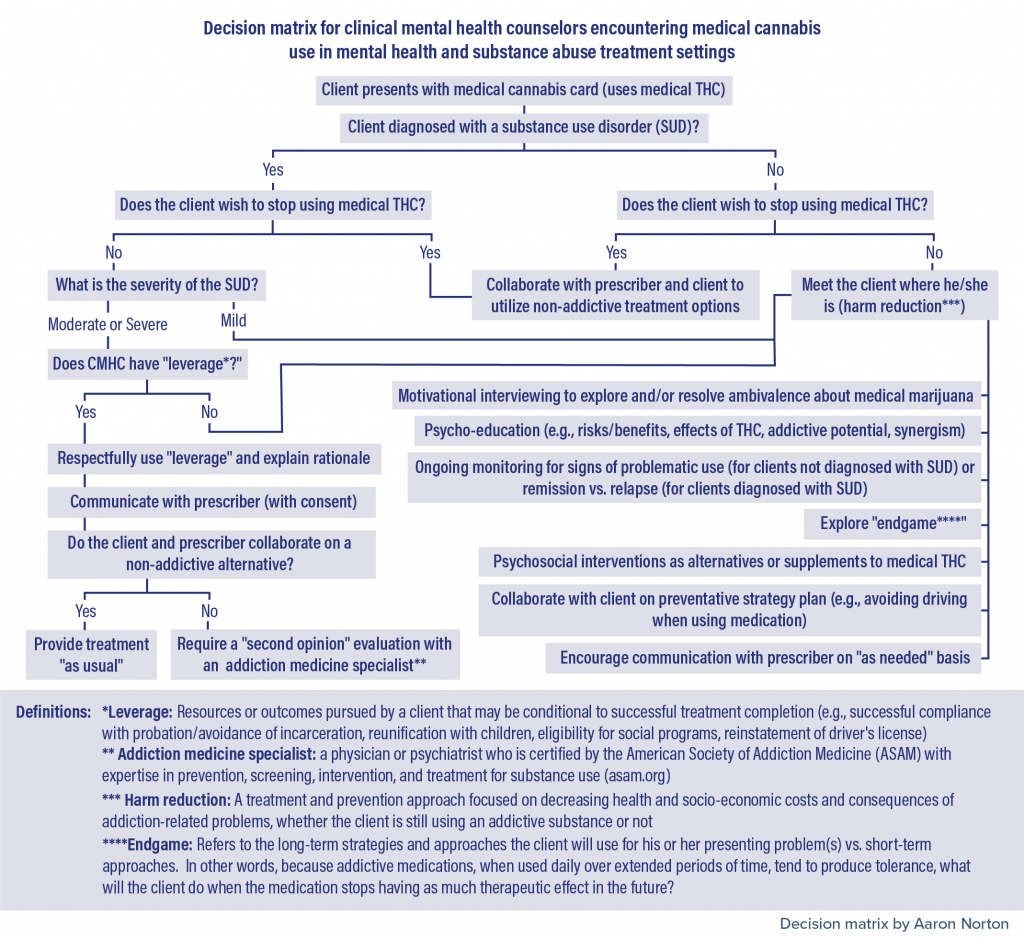

Norton’s experience — and frustration — with this scenario led him to create a decision-making matrix (see below) for counselors to use when discussing marijuana use with clients who have been prescribed legal cannabis for medical use.

When addressing marijuana use in counseling sessions, Norton suggests that practitioners focus on clients’ motivation to change and their attitudes toward stopping their use of marijuana. His model offers different treatment scenarios for clients who have and have not been diagnosed with a substance use disorder and for situations in which the counselor has leverage (i.e., resources or outcomes the client wants, such as the return of a driver’s license or child custody, that are conditional to successful treatment completion).

In the case of clients who want to stop using cannabis, the counselor can collaborate with and refer them to a physician to find an alternative treatment. For those who do not want to stop using cannabis, the counselor can take a harm reduction approach to make gains toward behavior change in other ways, Norton explains. This includes strategies such as using motivational interviewing to explore the client’s thoughts on continuing their marijuana use or co-creating a “preventative strategy plan” with the client to identify benchmarks such as avoiding driving while using cannabis.

A harm reduction approach can prompt growth and behavior change in clients even while they continue to use cannabis — and much more so than simply leaving it unaddressed, Norton emphasizes.

Taking a nonconfrontational and supportive approach

Many of the harm reduction techniques Norton includes in his decision-making matrix involve collaboration between the counselor and the client. This ensures the counselor meets the client where they are, he says, and increases the likelihood of positive behavior change.

Katharine Sperandio, Daniel Gutierrez, Alex Hiller and Shuhui Fan, co-authors of the April 2021 Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling article “The lived experiences of addiction counselors after marijuana legalization,” interviewed six professional counselors in Washington and Colorado (the first states to legalize marijuana for recreational use) who work with clients experiencing substance use disorders. They found that using a nonconfrontational, “motivational enhancement” approach with clients regarding marijuana use was more beneficial than addressing it head-on.

One participant in the study provided an example of a nonconfrontational approach. They broached clients’ marijuana use by framing it as a question: “Why do you think it’s a problem for you?”

The co-authors also learned that with the legalization of marijuana, practitioners are seeing an increase in client justification and rationalization of marijuana use and less acceptance that it can be harmful or problematic, particularly among adolescents. Many clients were found to be using legal marijuana to numb negative thoughts and emotions, ease chronic pain, cope with trauma and “as a substitute for alcohol or other drugs rather than seeking [counseling] treatment because it was so readily available.”

The study participants also reported that clients were “more likely to walk out of treatment” and less likely to communicate about marijuana use (even if it was a source of other problems) if they felt there was a policy or recommendation to decrease marijuana use.

When school students are facing discipline for marijuana use, addressing it in a supportive way is the best approach to discourage those students from returning to risky behaviors, McClain says. When possible, it is helpful to involve the student and their parent(s) or guardian(s) as well as the school counselor and administrator to ensure that the student has a support system and reentry plan that doesn’t involve marijuana use and related behaviors, he says. Such a plan might include regular check-in conversations with a school counselor.

Taking a holistic approach, rather than only punishing, avoids setting the student up for failure and ensures that all of the student’s stakeholders are on the same page, McClain adds.

“We want to make sure they have a support system, including a counselor, to turn to for help. As much as we can surround them with support, hopefully the outcome will be better,” says McClain, who has worked as a school counselor for 17 years.

Case example

An adult woman came to see Britton for PTSD after experiencing sexual trauma. The client was experiencing intense flashbacks, having trouble sleeping and struggling with chronic pain. Britton surmised that the pain was related to her trauma because the client held her trauma in her body.

Britton used dialectical behavior therapy with the client, who made a small amount of progress in the first year but eventually stalled despite staying engaged in sessions and showing a willingness to try exercise and other actions that Britton suggested. The client continued to be plagued with sleep difficulties and night terrors, even while using a prescription sleep aid. Britton continued to co-treat the client while referring her to a practitioner who specialized in eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy.

“It took her a long time to forge trust; it took her several months to even tell me what happened. Once we got to that part, we started making some progress, but then she hit a wall,” Britton recalls. “Not only was the EMDR not helpful, but she [also] found it upsetting and she started going downhill, discouraged that she’d ‘never get better.’ … She felt really stuck and scared, and we weren’t making a whole lot of progress. The more she couldn’t sleep, the worse her symptoms got.”

Eventually, the client brought up the possibility of trying medical marijuana. Britton responded by saying that she couldn’t advise her on whether it would be effective, but she could write a letter confirming that the client had PTSD in case she wanted to pursue obtaining a medical marijuana card.

Ultimately, the client did receive a medical marijuana card and began using cannabis to alleviate her pain and trauma symptoms.

“It wasn’t a miracle cure. … She still presented with some trauma symptoms [while using medical marijuana], but it helped her sleep, and that was huge,” Britton says. “It didn’t ‘cure’ her, but it took the edge off so she could look at things a little clearer, and she started feeling some hope [after] feeling so deflated, so defeated. It gave her the energy to work toward some other behavioral treatments.

“She wasn’t drug seeking; she was seeking symptom relief. It helped enable her to do the work that was in front of us [and] gave her the braveness to face it. It was just part of [her treatment]. It wasn’t the full answer, but I was glad we tried it.”

Bias management

The counselors interviewed for this article agree that clinicians have a responsibility to seek training, consult with colleagues and stay up to date on the regulations regarding marijuana in their area as well as the ways that its use — and misuse — can affect mental health.

At the same time, counselors are ethically bound to keep their personal views about marijuana (and all substance use) out of their counseling work, St. Amant notes.

“Substance use exists on a spectrum, and just because someone uses legal or illegal substances does not mean they have a substance use disorder,” she says. “Counselors must be careful not to impose their own values about substances use on their clients or project their own beliefs onto others. When the use of substances is conceptualized as a moral concern or a personal failing, we add to the stigma of substance use. Our attitudes must remain nonjudgmental and nonmoralistic when it comes to substances.”

****Can counselors use legalized marijuana?

In states where marijuana use is legal for medicinal or recreational purposes, counselors have the right to use it on their own time, but they also have the ethical obligation to ensure that it does not cause an impairment to their clinical performance and their relationship with their clients. They can do this by approaching it the same way they do with alcohol use.

Counselors can ethically use legal substances as long as they do not perform clinical duties under the influence, the use does not impair their ability to function (e.g., seeing clients while experiencing a hangover or the prolonged impacts of the substance) and they are able to use the substances responsibly (e.g., not driving under the influence). If counselors choose to use legalized marijuana, one should be aware of how long the effects last (which can linger into the next day for marijuana) and ensure that no pictures are posted of them using the substance on social media.

If counselors have difficulty controlling their use or if it affects their health or clinical abilities, they should seek out an evaluation to see if they could benefit from treatment, and they should refrain from providing clinical care until it’s determined that they can do so safely and ethically.

Our ethics are founded upon ensuring client safety and preventing harm to those we serve, so our clients’ right to be protected from potential harm by their counselor using substances supersedes our personal freedom during the time in which we are working with them. Yes, we counselors are adults who are allowed to live our lives how we personally see fit, but, no, our personal choices cannot come at the cost of our clients’ safety.

See Standards C.2.g. and A.1.a. of the 2014 ACA Code of Ethics at counseling.org/ethics.

— Emily St. Amant, counseling resources and continuing education specialist for ACA

**** Bethany Bray is a senior writer and social media coordinator for Counseling Today. Contact her at bbray@counseling.org. **** Opinions expressed and statements made in articles appearing on CT Online should not be assumed to represent the opinions of the editors or policies of the American Counseling Association.