The High Cost of Human-Made Disasters

By Lindsey Phillips

March 2018

The stories of the aftereffects of human-made disaster have become all too familiar: a refugee forced to make a dangerous journey to find a new home; the soldier deployed thousands of miles from home for months at a time; the person who finds his or her world turned upside down when a shooter enters the room and begins firing. It’s not surprising, then, that according to a report by the American Psychological Association, in 2017, 60 percent of Americans felt stressed about terrorism and 55 percent felt stressed about gun violence.

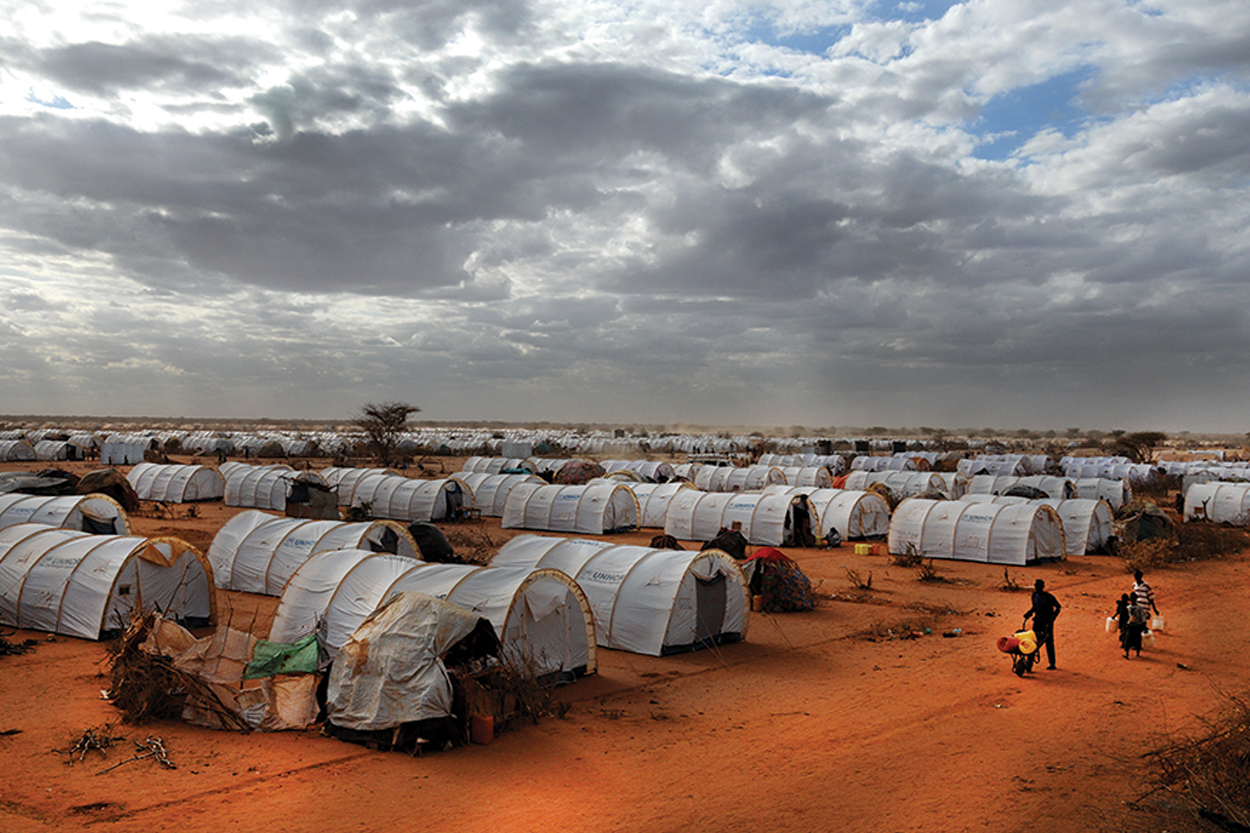

In addition, refugees fleeing war-torn countries have created an international crisis, and, among other things, they aren’t getting the mental health care they need. The International Medical Corps found that 54 percent of Syrian refugees and internally displaced populations in Syria, Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan suffered from severe emotional disorders, including depression and anxiety.

The increase in human-made disasters raises a question for counselors and others: Does the type of disaster — natural, human-made or technical — affect the severity of the trauma or the counseling approaches used to treat it? Devika Dibya Choudhuri, an associate professor at Eastern Michigan University, says sufficient research indicates that when human agency is involved, the disaster has a more traumatizing effect. Although natural disasters are traumatizing, there is often a huge response of communities taking care of one another, which tends to be a restorative factor, she explains.

“With human-made disasters … the aftermath is also conflicted,” says Choudhuri, a licensed professional counselor and American Counseling Association member who presented at the ACA 2017 Conference & Expo in San Francisco on group interventions in the aftermath of violence, terrorism and dislocation. “Most [refugees’] … traumatizing stories are not just [about] the original trauma. … The journey after is so profoundly traumatizing as well because not only are they ungrounded from the loss of home, but then all of these additional wounds are made. There is no safety anywhere, as opposed to that sense [after a natural disaster that] people are coming forward to help.”

Rebuilding trust, regaining control

Choudhuri, who worked with Cambodian and Bosnian refugees in the 1990s and has worked with Iraqi and Karen refugees since the 2000s, points out that survivors of human-made disasters are fighting on two fronts: struggling to survive in their environment and engaging in an inner conflict where the original strategies for survival during the trauma are no longer helpful. Thus, when it comes to trauma and human-made disasters, counselors should focus on restoring a client’s sense of control, not safety, she advises.

Hannah Acquaye, an assistant professor of counseling at Western Seminary in Portland, Oregon, works with refugees from war-torn countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq and parts of Africa. She finds that for refugees from countries where neighbors are fighting neighbors, the trauma is unique in terms of feeling a sense of betrayal. If the person holding the gun and causing the devastation is someone they know and used to play with growing up, then the trauma becomes especially troubling, she says. “It affects the way they trust people … and makes it harder to build a community back,” explains Acquaye, an ACA member whose research focuses on refugee trauma and growth.

Thus, rapport and trust are crucial for survivors of a human-made disaster. According to Mark Stebnicki, professor and coordinator of the military and trauma counseling certificate program in the Department of Addictions and Rehabilitation Studies at East Carolina University (ECU), empathy and listening are critical elements of establishing rapport and gaining the trust of these clients.

Establishing a therapeutic alliance can be problematic, however. Counselors often learn to build a therapeutic alliance by offering warmth and connection and by encouraging clients to tell their stories, Choudhuri points out. But for individuals who have experienced a “traumatizing offense through human agency … the betrayal and abandonment and loss of trust during the process gets triggered by the very warmth of the connection,” she explains. Counselors will often experience that after making a connection and getting the client to open up, the client never shows up again or ends up in the hospital, Choudhuri says.

Before uncovering the trauma, counselors must help rebuild and ground clients so that they will have resources to address the trauma, Choudhuri argues. “Rather than creating a therapeutic alliance, it’s about rebuilding the kinds of ways in which people can take care of themselves so that they don’t require the therapist to do that,” she explains. In fact, she advises that counselors should work with survivors of human-made disasters as if they will have only one session together. The first few sessions should focus on techniques that will help clients function in case they don’t return, she says.

One way counselors can help clients become autonomous is by providing them with tools to regulate their emotions. Somatic and emotion regulation techniques allow survivors of human-made disasters to notice their triggers on a sensorial basis and use their brain to counter this negative trigger, says Choudhuri, a certified eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapist. In a sense, their brain becomes an ally, rather than an obstacle or hindrance, in their recovery.

One of Choudhuri’s clients suffered trauma after being held captive and tortured for several days. Smelling the cologne worn by one of his captors would trigger the client. After identifying this sensorial trigger, Choudhuri set out to counter it. She discovered that the client found lavender essential oil calming, so she directed him to take in the lavender scent anytime that he encountered the smell of cologne. The process works on two levels, Choudhuri notes, because “it’s addressing the sensorial piece, but it’s also giving control back [to the client].”

Choudhuri also finds that traumatic resilience is important when working with survivors of human-made disasters. Many resourcing and grounding techniques that counselors use can also make clients more resilient in the face of ongoing trauma, she notes. For example, Choudhuri finds the container technique helpful for her clients: She tells clients to think of a container with a secure lid (e.g., a jar, a jewelry box) and then to use that container to mentally store the parts of the trauma that get in their way and prevent them from moving forward.

Group work is another resource that can help survivors of human-made disasters rebuild a sense of trust. At the same time, Choudhuri says, “group work is really challenging, particularly for [people] who have had human-made disasters, because other human beings are a source of threat [to them].”

In fact, Choudhuri is careful to avoid touching clients who have been hurt by other human beings. Instead, she teaches clients how to give themselves a comforting touch. For example, she uses the butterfly hug method (clients cross their hands over their chest and alternately tap their hands to a heartbeat cadence) while she facilitates thoughts of being safe and loved. This technique works well with children and is one that clients can do themselves when they are upset, she adds.

Rather than asking individuals to share their trauma in groups, Choudhuri suggests having them process it in a way that allows group members to provide comfort to each other, thereby helping restore a sense of control, trust and efficacy. For example, counselors could have individuals teach each other how to engage in deep breathing. “It allows for people to feel empowered to … not just be on the receiving end but also on the giving end,” Choudhuri explains, “and then they’re giving something that they themselves are learning, which helps them learn it better.”

From Stebnicki’s perspective, groups not only allow counselors to identify people who need more individualized treatment but also provide a safe space to verbalize and normalize survivors’ feelings (e.g., anxiety, depression, grief, sleeplessness) about an event and prepare them for the forthcoming weeks. “If you get [clients] to open up and share feelings [in a group], then the group itself is your own best source of support because they can normalize what that scary event was like,” he says.

Bridging cultural differences

Stebnicki acknowledges that working with people who are culturally different from the counselor can be challenging. Clients who are refugees, immigrants and asylum seekers may pose an even greater challenge because American counselors are often far removed culturally from individuals from war-torn countries such as Syria and Afghanistan, he adds. But successful treatment relies on understanding clients’ cultures and how they heal, he asserts.

In some cultures, counseling as generally practiced in the Western Hemisphere doesn’t exist, so counselors shouldn’t force clients to share their stories, Acquaye says. Instead, counselors should focus on providing a safe, supportive environment and inform clients that they are in the moment with them, she advises.

Stebnicki, a member of both ACA and one of its divisions, the Military and Government Counseling Association, says that he distinguishes between civilian and military responses to human-made disasters. “Military is a culture unto itself,” he says. “Military personnel experience person-made disasters differently in that instead of detaching, isolating, running and going into shock like civilians do, they adapt and survive, and they aggress … [not] stress.” Unlike civilians, who typically respond to a shooting by running away, military personnel are generally running toward the gunfire, he points out.

At the same time, civilians and military personnel experience similar physiological, psychological and emotional responses to human-made disasters. However, military personnel also experience ongoing trauma stressors (such as multiple deployments) and generally do not undergo the full range of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms until after their deployment or military service ends, Stebnicki says. Thus, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders “measures PTSD, but mainly in civilian life because it doesn’t take into account this … repeated exposure to trauma which military [personnel] are exposed to,” he argues.

In addition, military personnel often cannot easily take advantage of mental health services in the same way that most civilians can because of the stigma that military culture places on it, Stebnicki says. Using these services can sometimes put their security clearances at risk, cause them to get demoted or have others in the military lose faith in them and their ability to lead, he explains.

Despite these difference, many counselors try to treat military personnel as civilians and do not recognize the distinctions between civilian and military mental health, Stebnicki says. To help address this issue, he developed the certificate in clinical military counseling at ECU. The course trains professional counselors on some of the unique cultural differences in diagnosis, treatment and services for members of the military.

Making meaning of human-made disasters

In the face of a human-made disaster or a large-scale political event, people often feel helpless, like a small cog caught in a big wheel, Choudhuri says. In such cases, the counselor’s aim is not to help clients find an answer to existential/spiritual questions of why the disaster happened but to help them figure out a meaning to these events that they can live with, she says.

Meaning making should also involve some degree of personal growth, Stebnicki notes. He says that counselors can determine whether clients have experienced posttraumatic growth by their actions: Are they taking their medications? Are they going to counseling? Have they reconnected socially? If the answer is no, then there is no growth, he says.

The counselor’s job, Stebnicki contends, is to provide tools and resources to help clients take responsibility for finding meaning and growing from the trauma. However, he points out, growth is painful, so counselors must prepare clients to take small steps toward identifying ways of feeling safe and ultimately finding meaning.

Acquaye actively celebrates her clients’ small victories because she believes it encourages them. She had one client who was a refugee who was depressed because she didn’t know how to communicate in her new culture. Acquaye asked her to try to leave her apartment each day and walk around for five minutes. When her client was successful, Acquaye jumped up and down in front of the woman to celebrate her progress. Taking this small step forward helped her client begin to sleep regularly again, Acquaye says.

Choudhuri looks for ways to address clients’ despair without trying to change their beliefs about what happened. She finds EMDR helpful because it allows people to process internally without having to give the counselor details about their trauma. At the same time, clients are able to arrive at a meaningful narrative about their experience. “It may not be my answer, but it’s their answer,” Choudhuri adds.

Choudhuri provides an example of a Syrian refugee who participated in EMDR therapy that involved drawing and processing his trauma. At the end of the session, he said that regardless of the terrible things that had happened to him, he realized that every night has a morning. “It wasn’t that he got an answer or that he had a solution,” Choudhuri says, “but he got what he needed — hope.”

For many clients, spirituality plays a large role in meaning making. If the client’s and counselor’s spirituality differ, then the counselor should find common ground to discuss spirituality, Acquaye advises. The majority of her clients are Muslim and Acquaye is Christian, so in session, they discuss the general concept of God and who is in control of everything. “We can’t explain why people do what they do, but we can hold on to somebody who is greater than people and know that some good may come out of that,” she explains.

Self-care and counselor fatigue

Clients’ stories of trauma, suffering and loss can take a toll on counselors, resulting in counselor burnout, compassion fatigue or empathy fatigue. The cumulative effect of seeing multiple survivors of human-made disasters and other traumas can start to deteriorate counselors’ spirit to do well and damage their own wellness, Stebnicki notes. For that reason, counselor self-care must become a priority when working with survivors of human-made disasters.

Stebnicki differentiates between empathy fatigue, a term he coined, and other fatigue syndromes such as burnout and compassion fatigue. He explains that empathy fatigue results from a state of physical, emotional, mental, spiritual and occupational exhaustion that occurs as the counselor’s own wounds are continually revisited through a cumulation of different clients’ stories of illness, trauma, grief and loss.

The major difference between these types of fatigue syndromes is that empathy fatigue has an added spiritual component, Stebnicki notes. Horrific experiences such as genocide and torture go beyond the range of ordinary human experience and affect the mind, body and spirit, he explains. Thus, it is crucial that counselors are properly trained to be empathetic and compassionate, he says. In addition, because people experience and define spirituality in their own individual ways, counselors must understand their clients’ views of spirituality to assist them in cultivating hope and psychosocial adjustment to their trauma.

Acquaye acknowledges that she didn’t initially realize how much the stories of her refugee clients would affect her. If counselors are struggling with counselor fatigue, they need to seek help to avoid harming their clients, she advises. “It’s not about me. … If I claim I’m an advocate for my refugee clients, then I should get over myself and ask for help, so I’ll become a better person for them,” she says.

Choudhuri says counselors must also guard against making another common mistake. Because refugees often have little meaningful support, they are incredibly grateful when they do receive it, and there can be a danger in that for counselors. “If [counselors] work long enough with [refugees], it gets really easy to feel like a savior,” Choudhuri admits.

“One of the things that trips [counselors] up is this belief of indispensability — that there is nobody else, so I have to keep doing it even if I don’t want to,” Choudhuri adds.

She also finds that working with clients who have survived a human-made disaster can bring out something of a competitive nature in counselors: They assume (often incorrectly) that if the client can deal with the trauma, then they can too because they are the counselor.

Among the possible signs of counselor fatigue syndromes that Stebnicki notes are having diminished concentration, feeling irritable with clients, feeling negative or pessimistic, and having difficulty being objective or compassionate. “We’re good as counselors at giving advice to others and helping facilitate self-care strategies, but we don’t do it ourselves. We need to take our own best advice and get help,” he advises.

Stebnicki has found peer support helpful when dealing with fatigue syndromes. He and other colleagues meet once or twice a month to vent and share their stories. In fact, he notes that it is common to have ongoing peer support on-site for counselors and first responders at large-scale human-caused disasters. These support groups allow counselors to discuss what they saw, how it affected them, how they are responding and how they are going to overcome it, he says.

Acquaye is thankful for her supervisors and own personal counselor who help her guard against burnout. “I have to remind myself all the time that I’m not God … so I can’t carry my client because sometimes the stories are so heavy that you can’t sleep at night,” she says. She realizes that carrying the burden of her clients’ stories will serve only to make her negative and ineffective as a counselor.

Many counselors are drawn to working with refugees because they want to help, but before jumping in, Acquaye says, counselors should understand what their strengths and limitations are. “Ask yourself [if] you have enough strength for the kind of stories they will throw at you. [If not], it doesn’t mean you are not good enough. It just means that that is not your area,” she says. “When it comes to refugee work … you are going to go through the trauma yourself, so you have to ask yourself, ‘Do [I] have what it takes to go through that?’”

Lessons learned

How can counselors prepare to handle the specific needs of survivors of human-made disasters? “Training to be trauma informed becomes key. … There shouldn’t be counselors coming out of counseling programs who don’t have a basic understanding of trauma,” Choudhuri asserts. Yet, she finds that counselors often report not knowing how to deal with trauma and disaster mental health.

Choudhuri thinks that one area of disaster mental health where training needs to improve is clinical competency. Often, counselor educators aren’t practitioners, which can be problematic because they don’t see the chronic nature of clients’ issues and thus don’t prepare adequately, she contends. She argues that counselor educators should stay clinically active — perhaps even working with survivors of human-made disasters — to keep their finger on the pulse of what is happening.

Of course, Acquaye admits that counselors are never likely to have all of the training they need to handle disaster mental health straight out of school. Many of the skills must be learned on the ground. She recounts a time when despite her training on refugee trauma and posttraumatic growth, a client’s story scared her to the point that she was shaking. She had to remind herself that even though she had no idea how to treat the client’s many issues on the spot, she needed to start by listening to the client and then figuring it out as she went along by researching and assessing the client’s needs.

What people consider to be trauma or traumatizing changes over time, Choudhuri notes, so the symptoms that veterans displayed after the Vietnam War are not the same ones that soldiers returning from Afghanistan and Iraq have displayed. Today, counselors also have to take into account the fact that there is more aggression digitally, and digital aggression distances people from the trauma, she adds. For example, drone warfare has changed the rules of war, allowing people to kill from a distance. This makes killing more impersonal and affects the mental health of drone pilots differently.

“As conflict becomes handled differently, [so does] the kinds of betrayals and ways in which people can be hurt electronically. … [People’s] sense of danger and risk become different than if somebody broke into [their] house. They’re related, but they’re different,” she says.

One mistake that counselors often make when working with clients is expecting a more intense early disclosure of the traumatic incident, Stebnicki says. Stebnicki worked as a member of the crisis response team for the Westside Middle School shootings in Jonesboro, Arkansas, in 1998. In the aftermath, he witnessed a counselor go up to a student, take him by the shoulder and almost shake him to force disclosure of what the student had just experienced. Counselors must remember that everyone heals at his or her own rate, so survivors of human-made disasters may not want to discuss their experiences immediately after the event, he says.

Stebnicki has also found that people’s experiences vary based on their proximity to the disaster’s epicenter. “We all differ in stress and trauma in terms of the pattern, the frequency, the exposure, the magnitude/intensity. So, in other words, we all turn our stress response on differently,” he says.

In working with refugees, Choudhuri has learned that counselors can’t assume to know the trauma. One of her clients had been married off by her parents while in the refugee camp to a man who raped her. Was the worst part of her experience being in the refugee camp, losing her home or being raped? Choudhuri discovered that for the client, it was that her parents didn’t love her enough to have chosen a better husband for her.

“It wasn’t the violence that drove her from her home, it wasn’t the destruction of her life as a schoolgirl, and it wasn’t even the brutality of her experience in the marriage,” Choudhuri says. “It was the sense of being betrayed by her parents.” Thus, counselors should remember that the focus of the work is not about the trauma but about the client, she adds.

Choudhuri has also observed that although disaster mental health professionals have developed ways to work with people immediately after a disaster, they often fail to implement this guidance back home. She argues that counselors don’t respond to the ongoing, everyday disasters happening in their backyards — the microaggressions and microassaults that wear people down as they try to overcome obstacles of systemic racism, chronic poverty, violence and substance abuse — in the same manner as they respond to large-scale events.

“If we can point to the singular event, we can be horrified by it and [respond] with compassion and helping, but when we live in it, we numb ourselves … to it because we feel helpless,” Choudhuri says.

“It’s difficult because we all want a place of safety … so it’s easier to go away somewhere and work on [disaster mental health] and then come back [home] and be safe,” she points out.

Counselors need to resist the urge to let trauma and disaster response fade into the background because of the discomfort these events can generate, Choudhuri argues. Instead, they must keep disaster mental health in the foreground and help rebuild communities and individuals affected by disasters, including those less obvious disasters happening in counselors’ backyards.