Essential skill development for meaningful social connection

September 2023

Research has identified the important role social connectivity plays in mental wellness. As trauma experts, we also recognize how attachment deficits and trauma wounds can impact components of making and maintaining relationships.

Attachment deficits may cause people to seek friends and partners who possess similar characteristics to their insecure attachment figures (such as partnering with abusive or emotionally unavailable individuals). These deficits may also result in people prioritizing their own attachment needs above the needs of others (as in the case of narcissistic relationships), or they may cause people to disregard their own boundaries to maintain relationships at any cost (such as in codependent relationships).

Unresolved trauma wounds can interfere with healthy connectivity when our survival defense systems are in overdrive trying to protect us from pain. We may react with hypervigilance and misinterpret interactions as potential threats, have difficulty trusting others, maintain rigid boundaries to avoid intimacy, or simply overreact or underreact emotionally to situations. Past trauma can cause both emotional and physiological changes that interfere with social connection. The survival reactions of fight, flight or freeze direct bodily resources to respond to the crisis and move away from activities unnecessary for immediate survival, such as digestion and higher-order functions of the prefrontal cortex. The limited operation of the prefrontal cortex reduces our capacity for executive functions such as reasoning and communication, which are important components in navigating relationships. This reduction in executive function can happen during an actual trauma or may be triggered by a sensation associated with the trauma.

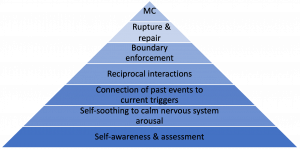

Counselors play a significant role in clients’ social skill development, increasing their potential to interact intentionally and not reactively from defensive responses. To help facilitate these discussions, we created the meaningful connection skills pyramid, a clinical tool counselors can use with clients who have insecure attachment and trauma histories (see Figure 1). This tool identifies six developmental skills that function in a progressive, developmental path toward meaningful connection and aid in intentional interactions: self-awareness and assessment, self-soothing to calm nervous system arousal, connection of past events to current triggers, reciprocal interactions, boundary enforcement, and rupture and repair.

In the following sections, we illustrate how counselors can use this tool with a hypothetical example: Alicia comes to counseling after she has a significant argument with one of her close friends. When she was scrolling through social media, she discovered that her friend attended a party without her. Alicia was so upset that she called her friend and accused her friend of not caring about her or their friendship. Then Alicia blocked the friend’s phone number and social media accounts. Alicia’s history of trauma has disrupted her ability to reason, communicate with her friend, hear other possible explanations for why she wasn’t invited or work through the relational rupture.

Increasing self-awareness

Self-awareness is a foundational skill in social connection. Socially intuitive individuals can remain aware of internal cues (i.e., awareness of internal states) and external cues (i.e., awareness of how they come across to others). Clients may be interoceptive, the internal awareness of what is happening in the body (e.g., heart racing, feeling a “pit” in the stomach), or neuroceptive, the ability to assess external cues of safety or threat in the context of relationships. For example, an employee may notice that their chest is tight as they approach an important performance review at work (interoception). When they enter the conference room, the boss provides cues of warmth and approachability by smiling, leaning back in their chair and greeting the employee in a friendly manner (neuroception); these cues enable the employee to intentionally engage in calming behaviors and remain grounded throughout the meeting. By increasing our internal and external awareness and recognizing when we are in a threat response mode, we can work toward feeling safe and changing our defensive reactions.

Counselors can use assessment tools to help clients notice, evaluate and describe their level of distress and social connection. Here are three self-assessments we recommend using with clients:

- Subjective Units of Distress Scale: This self-assessment tool allows clients to quantify their level of distress on a scale from zero to 10.

- Body scans: This method asks clients to pay attention to parts of their body and bodily sensations, starting with their feet and moving up to their head. Body scanning helps strengthen clients’ ability to practice interoception.

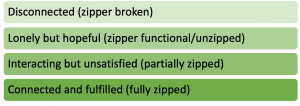

- Zipper screen: I (Lisa) created this tool to help clients quickly assess and describe their current perceptions of social connection (see Figure 2). Counselors ask clients, “How ‘zipped’ or connected to others do you feel right now?” Clients then respond using the metaphor of a zipper to describe how connect they feel: zipper broken (disconnected), zipper functional but unzipped (lonely but hopeful), partially zipped (interacting but unsatisfied) and fully zipped (connected and fulfilled). Clients can also create their own metaphors such as “zipper stuck in the fabric lining” to represent feelings of enmeshment and other distressful forms of connection.

- Window of tolerance: Clients can use this tool to evaluate their current arousal levels. The window of tolerance describes the optimal arousal zone (also considered “equilibrium”) between hyperarousal and hypoarousal, where clients remain regulated and the prefrontal cortex is active and functioning optimally. We recommend counselors use a color code to simplify the use of this tool: red for hyperarousal, green for optimal zone and gray for hypoarousal. With this method, clients do not need to remember the terminology; instead, they can respond using colors to indicate how they feel: green (“go” or move forward with treatment), red (too hot and need to cool down) or gray (lethargic and need to be energized). Counselors can teach clients how to expand their window of tolerance through emotion regulation activities and early identification of triggers.

We can help our hypothetical client, Alicia, increase her awareness of physiological cues of distress (interoception) and external cues of safety or danger (neuroception) using these tools. For example, the counselor could have Alicia take the Subjective Units of Distress Scale and reflect on the intensity of her distress at various points in her conflict with her friend (e.g., before seeing the social media post, during the phone call, after blocking her). In addition, the counselor could ask Alicia to identify what sensations she was feeling in her body at each of these points (e.g., stomach felt nauseous, chest was tight, face felt warm). Alicia could also consider what external cues contributed to her distress (e.g., the social media post, her friend’s tone of voice).

Calming the nervous system

It is common for clients with a history of insecure attachment or trauma to try to restore emotional and physiological equilibrium through maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. This can often prompt unhelpful oscillation between hyperarousal and hypoarousal.

For example, because of her traumatic experiences, Alicia finds herself constantly scanning her friendships for perceived rejection. This creates a state of hyperarousal and often intense symptoms of anxiety. To manage her hypervigilance, she drinks heavily in social situations in an attempt to calm her anxiety. The counselor can work with Alicia to help her identify her reactivity. Then she will be able to consider more adaptive emotion regulation strategies, including regulated breathing, progressive muscle relaxation and grounding exercises.

Connecting past events to present triggers

When clients have an emotional response that seems disproportionate to the present circumstances, they are likely reacting to past trauma wounds or attachment deficits. As clients learn to regulate their nervous system arousal, they can begin to cognitively connect their reactivity to specific triggers related to past events.

It’s understandable that Alicia would feel disappointed or confused when she discovered she was not invited to a party, but an amygdala-initiated survival response of fight, flight or freeze does not seem to correspond with the present threat. Once Alicia identifies her reactivity, she can explore past events potentially connected to her current trigger. For example, maybe past experiences of rejection led to negative core beliefs about Alicia’s self-worth, such as “I’m unlovable,” “I’m defective” or “I’m invisible.” In this case, modalities such as eye movement desensitization and reprocessing and cognitive behavior therapy can help clients such as Alicia identify origins of triggers, examine negative core beliefs associated with these memories, and instill more adaptive beliefs to promote healing from past trauma wounds and decrease reactivity to present triggers.

Engaging in reciprocal relationships

Insecure attachment can become trauma responses if the person has unmet needs in infancy and early childhood. Parental responses to infant distress create relational structures that affect how the infant learns to relate to their caregivers and others. Insecure attachment is characterized by chronic misattunement to a child’s needs or emotional experience and can be experienced by the child’s nervous system as a threat to survival. The child learns to adapt to this chronic misattunement through relational patterns such as attention seeking or overattending to the needs of others.

Attachment science has been helpful not only in understanding child-caregiver relationships but also in conceptualizing adult relational patterns. Without intervention, children with anxious, avoidant and disorganized attachment styles can continue to exhibit these patterns in their adult relationships, creating enmeshed, detached or volatile relationship dynamics. But with therapeutic intervention, clients can learn to build and maintain reciprocal relationships, which allows both the client’s needs and the needs of others to be honored and respected. Counseling can also help clients discern safe and unsafe relationships, decreasing the likelihood of repeating unhealthy relationship dynamics established in childhood.

Alicia can now identify her reactivity, practice adaptive self-soothing reactions and connect her triggers to past wounds so that she can begin to practice reciprocal relationships with others. For example, the counselor might suggest Alicia take the risk of planning a social event and inviting others to attend, rather than expecting that her peers will anticipate and act on her desire for connection.

Enforcing boundaries

Reciprocal relationships establish an environment in which boundaries can be set and maintained. Boundaries provide personal guidelines for multiple areas of our life, including our commitments, how we want to be treated by others and how we care for ourselves. Communicating boundaries effectively requires assertiveness, or the ability to clearly communicate one’s needs while respecting the needs and dignity of others. Practicing this skill often requires people to be brave because others may not be receptive to or respect one’s boundaries.

For example, Alicia’s desire for her friends’ approval often caused her to stay out too late, which disrupted her sleep and her ability to arrive at work on time. A personal boundary for Alicia may involve setting a curfew for herself and communicating this to her friends. By keeping her own arousal levels in check and assertively communicating her needs, Alicia creates an environment with less potential for relational harm and higher potential for resolution to relational conflicts.

Managing and repairing ruptures

Every long-term relationship will experience a rupture of connection because of conflict, miscommunication or simply a difference of opinion. How we manage the ruptures determines the level of intimacy and longevity of the relationship. Many people did not have healthy role models in childhood for managing relational conflict. Maybe they watched their parents engage in volatile disagreements or passively avoid conflict; both extremes can make conflict feel threatening and prompt people’s defense mechanisms to engage quickly. It is tempting to avoid conflict and detach from individuals at the first sign of relational difficulties.

Once Alicia has managed her reactivity, moved toward reciprocal relationships and practiced boundary enforcement, she can resist the urge to lash out or withdraw in response to conflict and tolerate the uncomfortable feelings that come from confrontation. Ideally, Alicia would be able to communicate her sadness and disappointment about being excluded from a social event to a safe and trustworthy friend and work toward repairing the relationship. The skills of distress tolerance and active communication enable clients to stay engaged long enough to make genuine repair attempts and invite them to use effective conflict resolution with their partner, friend or colleague. The ability to successfully navigate relational ruptures and repairs builds trust and increases the potential for long-term intimacy in relationships.

Counselors can also model this skill for clients within the therapeutic relationship. In the book Preparing for Trauma Work in Clinical Mental Health, I (Lisa) and Corie Schoeneberg discuss how to have difficult conversations with clients and how to repair the relationship when therapeutic ruptures occur. Regardless of the type of relationship, remaining in the window of tolerance enables us to repair ruptures without defensive reactivity so that we can protect the integrity of the relationship and foster relational intimacy.

Conclusion

The meaningful connection skills pyramid provides a treatment plan for helping clients improve their social skills by progressing along a developmental path. Improving client self-awareness and emotion regulation and their understanding of the connection between past events and current triggers are all foundational interventions for trauma work and other presenting issues, such as marital distress and workplace conflict. Higher-level skills such as reciprocity, boundary work and conflict resolution are invaluable for all relationships and settings. Regardless of trauma history or childhood attachment security, all clients can increase their well-being through improved ability to maintain social connection.

Lisa Compton is a professional counselor with over 25 years of experience. She holds a doctorate in counselor education and is a certified trauma treatment specialist. She is a full-time faculty member in the master’s and doctorate counseling programs at Regent University, an author and a conference speaker.

Taylor Patterson is a doctoral student in counselor education and supervision at Regent University. She is a licensed professional counselor who works primarily with adults with a history of childhood trauma.

Counseling Today reviews unsolicited articles written by American Counseling Association members. Learn more about our writing guidelines and submission process at ct.counseling.org/author-guidelines.

Opinions expressed and statements made in articles appearing in Counseling Today do not necessarily represent the opinions of the editors or policies of the American Counseling Association.