Climate in crisis: Counselors needed

By Laurie Meyers

August 2020

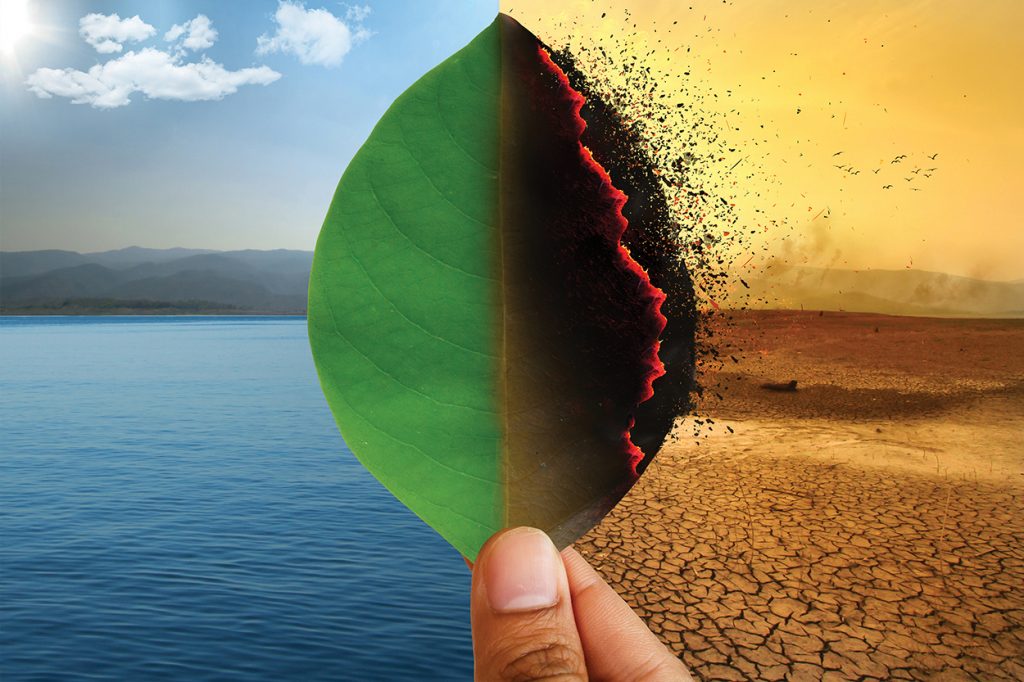

On a warming planet, some of the most rapid increases in temperature are being experienced in the Circumpolar North — the area within and, in some cases, just below the Arctic Circle. Overall, the average global temperature has increased by 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) since 1880. Two-thirds of that rise has occurred since 1975.

Since the 1990s, warming in the Arctic, in particular, has been accelerating. Researchers say the region is warming two to three times more quickly than the rest of the planet. In some areas such as Canada’s Labrador coast, the annual average temperature has increased as much as 3 degrees Celsius (5.4 degrees Fahrenheit), causing drastic changes in the weather, terrain and wildlife.

This coastal region is home to the Labrador Inuit people, who live in Nunatsiavut, a self-governing Indigenous territory with five communities — Nain, Hopedale, Postville, Makkovik and Rigolet — accessible only by airplane. The communities are not connected by roads. Instead, navigation is via paths over increasingly unstable ice, which is now prone to sudden thaws and pitted with holes. Unpredictable seasons and severe storms have also made it more difficult for the Inuit to get out on the land that has sustained them physically and spiritually for generations. Like other Indigenous peoples, the Labrador Inuit have faced displacement and forced assimilation. Traditional activities such as fishing, trapping, hunting and foraging are not just for subsistence; they are essential practices that undergird the Inuits’ culture and identity. Climate change has disrupted all of this, not only through changes in the ice, but through changes in the wildlife and plants.

But it goes even beyond that. Climate change is affecting the mental health of this region’s residents.

In 2012, the leaders of the communities of Nunatsiavut asked Inuit and non-Inuit researchers to conduct a regional study of the effects of climate change on mental health. More than 100 residents were interviewed as part of a multiyear study. The resulting report shed light on the strong emotions and reactions of the interviewees, who expressed fear, sadness, anger, anxiety, distress, depression, grief and a profound sense of loss.

One of the interviewees attempted to convey what the land represents to the Inuit: “For us, going out on the land is a form of spirituality, and if you can’t get there, then you almost feel like your spirit is dying.”

A community leader expressed an existential fear: “Inuit are people of the sea ice. If there is no more sea ice, how can we be people of the sea ice?”

Ashlee Cunsolo, a public health and environmental expert who was one of the lead non-Inuit researchers, believes that grief — ecological grief, as she and other researchers have dubbed it — is inextricably linked with climate change. She defines it as “the grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems and meaningful landscapes due to acute or chronic environmental change.”

A clear and present concern

The story of the Labrador Inuit is undeniably heart-rending. Even so, most people probably feel that scenario is pretty far removed from their own lives and losses. After all, as global citizens of the 21st century, our lives are increasingly virtual, and even if we enjoy the great outdoors, the idea of everything we are being bound to a particular land or place may seem alien.

Think about it a little more though. Whether our settings are urban, suburban or rural, most of us have geographic preferences, be they coastal, mountain, bayou, prairie, desert, forest or canyon. It might be where you live now or where you grew up, but it calls to you. And it has changed. That pond where you spent your childhood winters ice-skating no longer freezes hard enough to handle your gliding blades. Your favorite beach keeps losing feet of sand to the ocean. Ski season is now short on both time and fresh powder. Fire is prohibited at your favorite campsite. The city where you live has endured a summer string of 90-plus-degree days, leaving you longing for fall, but that season of cool, crisp air is increasingly elusive. The heat lasts well into September and October, as trees in your neighborhood stubbornly stay green — until they turn brown.

Austrian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht calls that feeling — a sense of missing a place that you never left because it has been altered by climate change — solastalgia.

“I think place can be really underestimated, but place attachment is such a part of who we are,” says Debbie Sturm, an American Counseling Association member who serves on the organization’s Climate Change Task Force. “If there’s harm in a place or threat to a place or loss of place, it is a significant loss.”

As an example, the diaspora caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was extremely traumatic, says ACA member Lennis Echterling, a disaster, trauma and resilience expert who provided mental health support in New Orleans in the wake of the storm. In some cases, people desperately fleeing the floodwaters and destruction were barely aware of where they were headed. Many of those who evacuated have never returned.

“There is still a population who have been separated from their homes — their sacred ground,” says Echterling, a professor at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. Although that phrase, sacred ground, is most often associated with tribal populations, Echterling believes it is true for all of us — that we all have an intrinsic attachment to place. And climate change will continue to separate people from their homes, he says, citing researchers who forecast that by the year 2050, an estimated 1 billion people worldwide will be climate refugees.

Even those who haven’t been displaced or experienced climate catastrophe may find it hard to avoid a creeping sense of existential dread — or ecoanxiety — as they witness or hear about extreme weather event after extreme weather event. On June 20, the temperature in the Siberian town of Verkhoyansk reached 100 degrees Fahrenheit, the hottest temperature ever recorded north of the Arctic Circle. Researchers say such an occurrence would be almost impossible (a once-in-80,000-years happening) without climate change caused by human activity. In recent years, wildfires have reduced entire California communities to ash, with citizens up and down the coast donning masks to protect themselves from a lingering pall of smoke. In 2018, Hurricane Florence turned Interstate 40 in North Carolina into a river. Hurricane Harvey struck Houston repeatedly over six days in 2017, leaving one-third of the city underwater at its peak. Approximately 40,000 Houston residents had settled in the city permanently after evacuating from Katrina more than a decade earlier.

Every year, the signs of a climate crisis grow more alarming, and the psychic toll can be traumatic. Psychiatrist Lise Van Susteren, an expert on the mental health effects of climate change, coined the phrase “pretraumatic stress disorder” to describe the fear that many individuals are experiencing about disasters yet to come.

Since 2008, the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University have been conducting national surveys biannually to track public understanding of climate change. The latest survey results, from November 2019, indicated that 2 in 3 Americans were at least “somewhat worried” about global warming, whereas 3 in 10 were “very worried” about it. A majority of those surveyed were worried about the potential for harm from extreme events in their local areas.

The mental health effects related to climate change extend beyond disasters such as hurricanes and wildfires. Research has indicated a link between rising temperatures and the increased use of emergency mental health services, not just in places that regularly experience hot weather, but in relatively cool areas as well. Higher temperatures have also been tied to increased levels of suicide.

As the ACA Climate Change Task Force reports in its fact sheet (currently under review), experts predict a sharp rise in mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance abuse and suicide, in addition to outbreaks of violence, resulting from coming climate crises. The task force views the counseling profession’s strengths-based approach and focus on resilience as essential to responding to those affected by climate crisis.

However, as part of a study that has not yet gone to press, Sturm, fellow ACA and task force member Ryan Reese, and ACA member Jacqueline Swank surveyed a group of counselors, social workers and psychologists about their personal and professional perceptions of climate change. Although Sturm, Reese and Swank found that these helping professionals were more likely than the average person to believe that climate change is real, very few felt the issue was relevant to their professional lives. Many respondents also said that they didn’t feel confident addressing issues related to climate change in their practice.

Climate change in the counseling office

Reese, a licensed professional counselor practicing in Bend, Oregon, believes that not knowing how to define — and, thus, recognize — climate concerns is part of counselors’ discomfort.

“What is climate change?” he asks. “Is it when you live in California and no longer have a home? … Is it a climate issue when a client is just talking about the general state of affairs and worrying about the world for their kids?”

Of course, there is also the matter of climate change being a polarizing topic, says Reese, an assistant professor of counseling and director of the EcoWellness Lab at Oregon State University-Cascades. When he is talking with clients about broader health and wellness and the topic of climate change comes up, sometimes they will tell him they think it is fake news. “What am I going to do?” Reese asks. “Am I going to impose my view? How do we find ways to introduce our wellness perspective without imposing?”

Reese’s practice is based on ecowellness, a model he co-developed with Jane Myers that revolves around a neurobiological relationship with nature. “The bridge here is, ‘Tell me about your relationship with nature,’” he says.

Reese says he does see a significant amount of ecoanxiety and fear of the unknown, especially among his adolescent clients. But they typically come in talking about depression.

Reese’s intake process includes questions about spirituality and life’s meaning and purpose. He asks clients about their outlook on the future, which is where their anxiety sometimes emerges. Questions about their relationship with nature often reveal the connection between that anxiety and their concerns about the climate.

If clients mention any angst about the environment, Reese asks whether they can unpack that a little more. He’ll follow up by asking questions about how a client spends their time outdoors, what their everyday access is to nature, where and how they feel most effective in nature, and whether they have any hobbies involving nature. He also encourages them to think about what role they can take on: “You mentioned being fearful about what your future is going to hold. What, if anything, can you do right now to address your concern about environmental crisis? … What is within your immediate grasp and control that you can do?”

Reese’s approach involves seeing what the individual’s broader landscape looks like and what their interests, passions and resources are. He urges his clients to get creative and often suggests that his adolescent clients take some kind of action at school, such as starting a recycling program. One of his adult clients took the action step of buying an electric bike and not driving his car as frequently to lessen his impact on the environment.

Reese also helps clients connect their hobbies with environmental action. For instance, if they like skateboarding, he’ll ask them what kind of impact they think that has on the environment. That may lead them to taking the action step of picking up trash around the skate park.

“It’s looking at what is the way we can increase self-efficacy in response to the environment so that it’s not abstract,” he says. “This is something I can engage in and learn and sustain this particular activity for myself and other people.”

Reese also asks clients to educate him about their activities. “For example, mountain biking is huge in Bend, but I don’t know anything about it. … What is the environmental impact? Oh, you don’t know either? Where can we find out?”

Climate change as social justice

ACA’s Climate Change Task Force notes that the resulting trauma from climate change has been and will continue to be experienced disproportionately. Black, Indigenous and people of color (and their communities), children, pregnant women, older adults, immigrants, individuals with limited English proficiency, those with disabilities, and those with preexisting and chronic medical conditions are all more likely to be affected by climate crisis and to have fewer resources to cope with its impact.

In September, the Gulf Coast will mark the 15th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, one of the most powerful Atlantic storms on record. It wrought widespread devastation and flooding, including the overflow and eventual break of the levee system around New Orleans. As a result, 80 percent of the city was submerged underwater.

New Orleans and Katrina are important to the discussion of climate change as a social justice issue for a number of reasons, says Cirecie West-Olatunji, a past president of ACA who now lives and works in New Orleans. “Katrina was our first uber-disaster related to climate change,” she says. “It informed the world and was a global example of what was to come.”

West-Olatunji provided disaster mental health assistance in the aftermath of Katrina. “I could see the gaps,” she says. “The normal [disaster] response was not going to be sufficient.” Specifically, she recognized that the recovery period would be lengthy, the trauma and mental health challenges extensive, and the reconstruction resources unequally distributed.

Foreshadowing the 2017 tragedy of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, the federal government’s response to Katrina was inadequate. It highlighted an essential barrier to recovery, namely that “whatever disparities exist prior to a disaster will be exacerbated post-disaster,” says West-Olatunji, an associate professor and director of the Center for Traumatic Stress Research at Xavier University of Louisiana.

Racial injustice, economic instability, and government funding for economic development that was distributed to certain communities and not to others were among the factors that magnified the physical and mental damage left behind by Katrina. And those factors continue to hinder recovery today. “Fifteen years later, and New Orleans is still in trauma mode,” West-Olatunji asserts.

There were multiple levee breaches, but only one adjacent neighborhood — the historically Black Lower Ninth Ward — was all but written off from the beginning of the recovery period, West-Olatunji says. Many of the residents owned their homes but faced multiple barriers to rebuilding. One of the most significant factors was discrimination in the distribution of Louisiana’s “Road Home” rebuilding funds. According to the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center (one of multiple plaintiffs in a lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the state of Louisiana), the program’s own data showed that Black residents were more likely than White residents to have their grants based on the much lower prestorm market value of their homes rather than on the actual cost of repair. Other displaced residents were unable to return and now cannot afford to pay their homeowners taxes, West-Olatunji says.

In the Lower Ninth, what’s left is an economic and food desert, with virtually no stores beyond a few mom and pops and only one school, she says. Developers have bought up properties, and instead of properly renovating them by gutting and bleaching the houses, in many cases they have simply repainted, leaving renters exposed to toxic mold.

In addition, much of what has been done to “rebuild” New Orleans has rendered it unlivable for those with low and modest incomes, West-Olatunji says. The city bulldozed public housing, and rent has skyrocketed. All of the city’s schools are now charter schools, which essentially makes them private schools that don’t answer to anyone other than their shareholders, she explains. “Kids are bussed all over the place … having to come out —unaccompanied — before daylight to find their way to school.”

New Orleans’ primary industry of tourism afforded a modest living to a significant number of residents for many years, West-Olatunji says. Pre-Katrina, that income could purchase a moderately priced house and even allow families to send children to state schools for higher education. Today, she says, the city is “assailed by outsiders and carpetbaggers who buy up properties. … We went from majority home ownership to rentals and Airbnbs.”

New Orleans is also a much whiter city now. Although most of the White residents who fled the city due to Katrina have returned, approximately 100,000 fewer Black people currently live in New Orleans than did before late August 2005.

West-Olatunji says there is a frequent refrain from the Black citizens who remained or returned: “I survived Katrina only to deal with the coronavirus and with the latest police brutality.”

“The trauma of Katrina was an overlay to existing and continuing stress and racial events,” she says. “It makes it really difficult to recover. … People are emotionally exhausted.”

Climate change should be of great importance to counselor practitioners, West-Olatunji says. “It’s influencing people’s behaviors and their possibility of choices. It narrows choices and creates barriers for living. Our job is to assist people in living abundantly. Climate change isn’t making that easy,” she says.

ACA member Edil Torres Rivera, a professor of Latinx studies and counseling at Wichita State University in Kansas, believes that climate change is still too frequently dismissed as a hoax. “Climate change is something that is real and … has implications for mental health,” he says, “particularly for populations like poor people, Indigenous people and people of color.”

Anyone who doubts that need only visit Rivera’s home island of Puerto Rico, where, three years after Hurricane Maria, people are still trying to recover. He says the urgent nature of the climate crisis is a primary reason that he joined ACA’s Climate Change Task Force.

In line with what happened in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, Hurricane Maria drove many people out of Puerto Rico, and those who remained faced multiple challenges, particularly around securing federal relief assistance and dealing with severe infrastructure deficits. Most critically, the island’s electrical grid was decimated, and it took approximately 11 months for power to be restored to everyone who lost it. But even now, Rivera says, it is still common for people to lose power for several hours whenever it rains. And this past January, a major earthquake left most of the island without power again for several days.

The trauma of Maria was compounded by the stress of the earthquake, which has been magnified even further by the coronavirus pandemic. “People are desperate,” Rivera says.

Many children in Puerto Rico are still terrified when it rains heavily and the wind rises, he continues. And since the earthquake, people are often hesitant about sleeping in their houses, so they stay in tents. This scenario will pose a major problem when a hurricane comes, Rivera says.

This past summer in Puerto Rico has been particularly hot, with some days reaching 103 degrees Fahrenheit. Rivera says this is higher than the norm when he was growing up and asserts that it again points to the effects of climate change. Typically, on hot days, people go to the beach to cool off. But the need to physically distance because of the pandemic has largely eliminated that option. Still, there are thos who, given the oppressive heat, would rather take their chances with possibly being exposed to the coronavirus. Another way that people cool off when it is hot is by having a beer, Rivera points out. He says that climate change has had a hand in sending both drinking and domestic violence rates through the roof for several years. The forced proximity of the pandemic is only exacerbating those trends, he adds.

Building resilience

Professional counselors “need to be involved and aware,” West-Olatunji says. “We can’t sit back and say that [climate change] has nothing to do with counseling.”

In fact, the counseling profession uses a holistic, ecosystemic perspective that looks at all the factors that influence behavior, she emphasizes. To take on climate change, counselors must broaden that model and consider structural interventions that target groups of people and focus on prevention. “Our discipline has always thought that prevention was at the core of wellness,” she points out.

West-Olatunji sees a great need for climate change literacy, noting that the people who most need knowledge about the climate crisis — because it is most likely to affect them either directly or indirectly — are also the least likely to have it. Vulnerable communities need to be given more information about how they can mitigate their risk and protect the health and safety of their citizens, she says.

Counselors can assist communities in building climate resilience by using their skills as facilitators to bring people together and help them work effectively as a group, says Mark Stauffer, a member of the ACA Climate Change Task Force. These groups don’t necessarily have to be focused specifically on climate change, he says. They could be formed to advocate for community needs, such as the right to clean water, or something more fun, such as establishing neighborhood gardens.

The essential aspect is to do the group work and to keep bringing people together, he says. “People coming together in times of need — we need to start practicing that now,” emphasizes Stauffer, the immediate past president of the Association for Humanistic Counseling, a division of ACA.

If counselors are personally concerned because their communities are not focused on climate change, Stauffer suggests they host a meeting of people who are interested in the topic. “See what people are thinking and where they want to go,” says Stauffer, a member of the core faculty in Walden University’s mental health counseling program. “It’s a process, but that’s the good part — connecting and building ongoing relationships. … People in the community need to get used to working together. The dialogue is just as important, if not more important, than the work.”

Stauffer thinks that counselors can play a key role in facilitating a new way of being in communities together. He believes that Western society has been living in a kind of empire culture, focused on what can be extracted. The mindset that started with Rome extracting treasures for itself from Europe and then Europe extracting treasures from its colonies has evolved into this sense that survival is about grasping and eking out a living by oneself, he says.

Stauffer says that our collective disaster survivor visual seems to be someone holding an AR-15 rifle in the air, surrounded by their supplies. “That’s not where we find joy,” he says. “Other cultures have found that surviving and being sustainable is something that we can do together.”

We need to find a way to be a part of the Earth in a generative way, Stauffer emphasizes. “The wild is not something to dominate and be afraid of,” he says.

Sturm, an associate professor and the director of counseling programs at James Madison University, urges counselors to get involved by finding out if their communities have climate resilience groups. Counselors who are unsure of where to start can bring themselves up to speed by using the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit (toolkit.climate.gov), a comprehensive resource that explores community vulnerabilities and climate resilience efforts.

Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications and Guidance, a 2017 report published by the American Psychological Association, Climate for Health and ecoAmerica, suggests several strategies for mental health professionals interested in promoting community well-being and helping to mitigate climate-related mental health distress. Among the strategies recommended:

- Assess and expand community mental health infrastructure.

- Reduce disparities, and pay attention to populations of concern.

- Engage and train community members on how to respond.

- Ensure distribution of resources, and augment with external supplies.

- Have clear and frequent climate-mental health communication.

“Find out who is doing this in your area. Our voice has to be at the table to talk about trauma,” stresses Sturm, who is also currently earning her master’s degree in environmental advocacy. “Counselors think this is important, but they’re not doing it. … We’re not reaching out in our communities as a profession to be part of the discussion.”

****

Laurie Meyers is a senior writer for Counseling Today. Contact her at lmeyers@counseling.org.

****

Opinions expressed and statements made in articles appearing on CT Online should not be assumed to represent the opinions of the editors or policies of the American Counseling Association.