Destined for Counseling

By Melanie Padgett Powers

January 2024

Richard S. “Rick” Balkin, PhD, LPC, was finishing up his student teaching in his last semester at the University of Missouri. In a few short weeks, he would graduate with his bachelor’s degree and become an English teacher. But after four years of study, once he began student teaching, he realized being in the classroom was not his passion.

What Balkin truly enjoyed was the interaction with his teenage students. “I liked the critical thinking that went on when you teach reading and literature and the thoughtful processes that were a major focus in English education,” he says. “It was an interesting way to connect with students.”

He started thinking about careers that would allow him to maintain a connection with adolescents. This led him to realize that becoming a school counselor may be a better fit. So, he asked his teaching supervisor: “What do you think about school counseling?” Instead of replying, “You’re about to graduate!” his supervisor said, “You’d be wonderful at that.”

Balkin stayed on at the University of Missouri to get a master’s degree in school counseling. (He earned his doctorate later at the University of Arkansas in his home state.) A few faculty suggested he should be working on the clinical side, but he stuck with school counseling at the time.

After he earned his master’s, he was hired to work at an alternative school. Six months later, he was recruited to work in an adolescent unit at a psychiatric hospital. “I thought that would be perfect. That would be centered on what I enjoyed most about working with adolescents,” he says. “And so I went and did that for seven years.”

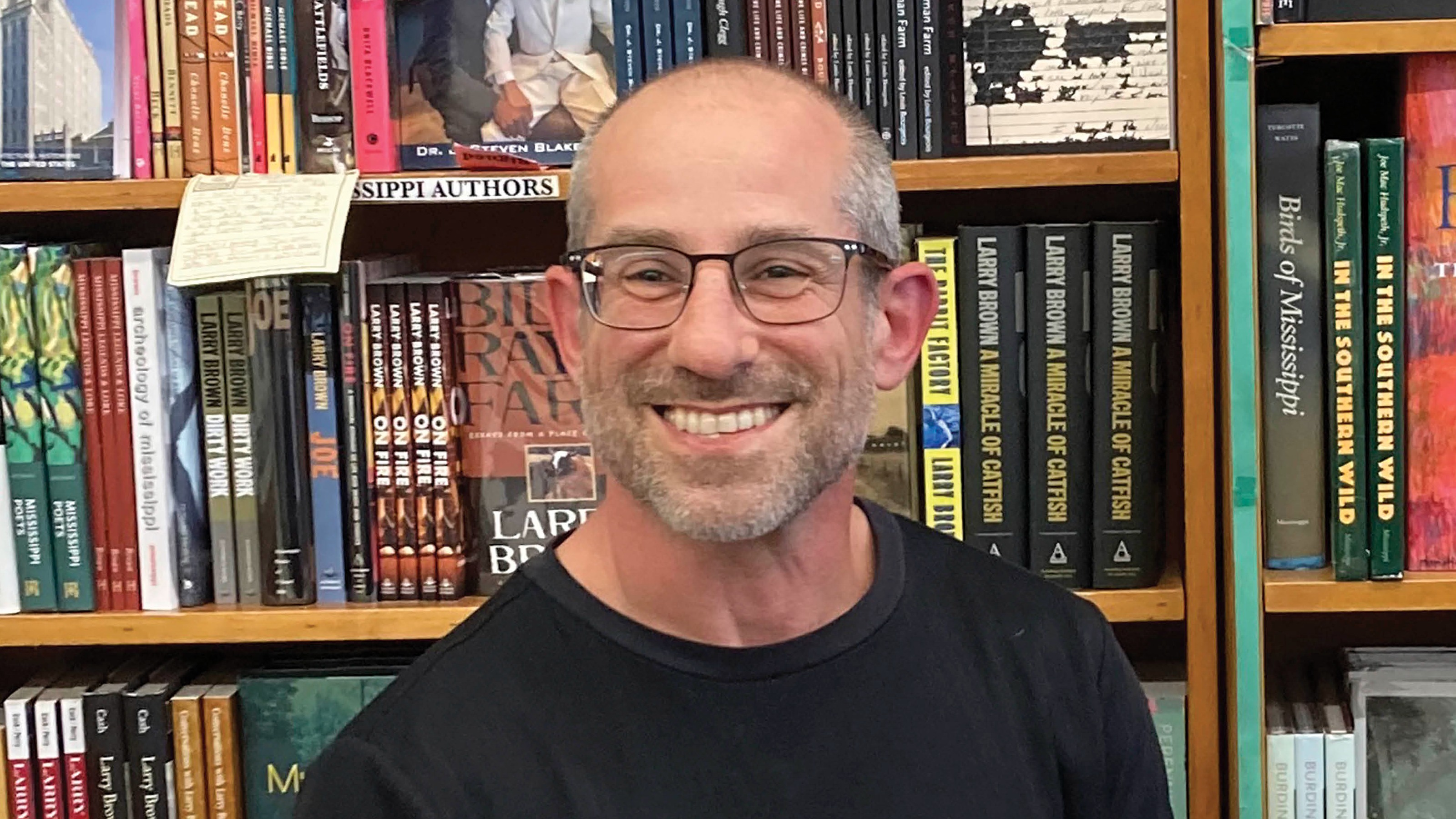

Balkin is now professor and department chair of leadership and counselor education, as well as coordinator of educational research and design, in the School of Education at the University of Mississippi. Over the past 30 years, he has followed his interests and passions wherever they might take him, creating a rewarding career that has included working with teenagers in crisis, helping underserved populations and becoming an expert on practicing forgiveness.

Balkin is an ACA Fellow and the author of Practicing Forgiveness: A Path Toward Healing as well as Counseling Research: A Practitioner-Scholar Approach (the latter published by ACA). He is also a former editor of ACA’s Journal of Counseling & Development and a past president for the Association for Assessment and Research in Counseling.

Developing a Model for Forgiveness

Early in his career, at the psychiatric hospital, Balkin was working with a 16-year-old girl who had been sexually abused by her father, who was denying the allegations. During a family session with the girl and her mother, the mom turned to her child and said, “You know, as a Christian, you have to forgive him.”

Balkin looked at the mother and said, “Wouldn’t that be convenient for you?” The mom “was pretty upset with that comment, and the family session didn’t go very well,” he recalls. “But this idea of, as a Christian, you have to forgive him really bothered me.”

Balkin is Jewish and wondered if that concept of forgiveness was actually a part of Christian theology. Even if it was, he says, “it seemed like a very unsupportive and hurtful comment.” The session stuck with Balkin over the years as he continued to counsel adolescents. About five years later, at services for Yom Kippur — the Day of Atonement and the most solemn day in the Jewish calendar — he was learning more about the Jewish conceptualization of forgiveness. Judaism has three types of forgiveness: spiritual, restitution and “mechilah,” which is the wiping away of debt. Balkin thought back to his teenage client and what her mother had said.

“We reach a point that what I want from you, I’m not going to get so you don’t owe it to me anymore,” he explains. “I release you from this debt. But I still think you’re a jerk and I don’t have to have a relationship with you.” This concept of forgiveness can help people stop carrying the burden of a person owing them something that they’re never going to get, he says. He thought: “How empowering. And we don’t talk to our clients about that.”

He approached colleagues to begin working on a Forgiveness Reconciliation Model. “What this model contributes is the idea that not every relationship is repairable — and it’s not always safe to go back into a relationship that’s been harmful,” he explains. “Reconciliation has to be a separate piece of this.”

After Balkin began to present the concept and receive positive feedback, he worked on collecting data to validate the model. That became the Forgiveness Reconciliation Inventory. “It spawned an area of research and a book, and it’s just been exciting to be able to contribute to the counseling profession and client care in this way.”

Another of Balkin’s contributions to the field is the Crisis Stabilization Scale, a clinician-rated instrument first published in 2014 for adolescent clients who were a danger to self or others. The model helps clients commit to safety, identify problems that got them to this point, process coping skills and commit to a follow-up plan, with the goal of moving to a less-restrictive level of care. Counselors can use the scale to explain to insurance companies why they should cover in-person psychiatric hospital care until the client meets specific goals related to crisis stabilization. For his work with adolescents in crisis, Balkin was awarded the 2019 ACA Extended Research Award.

Creating a Tele-Mental Health Center

Balkin is the first to admit he’s not a “technology person.” But when the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, counselors could no longer meet clients in person, plus graduate students were unable to meet their clinical experience requirements.

Balkin proposed creating a tele-mental health solution at his university. He obtained a grant from Mississippi’s Governor’s Emergency Education Response Fund, which was supported by federal COVID-19 emergency response money, to create a tele-mental health center on the University of Mississippi campus. The center provided mental health services across the state to public school children — who were unable to access school counseling services during lockdown and virtual schooling. The funding also helped build the tele-mental health infrastructure and train counseling students on how to use it and meet their certification requirements. (Balkin secured external funding after the governor’s grant ended to keep the center going.)

Even though face-to-face counseling is now available, 52% of the center’s counseling is still done virtually. It has expanded mental health counseling accessibility in Mississippi, one of the most economically disadvantaged states in the country, particularly the Delta region. “Being able to provide counseling services for a very disenfranchised population has been really important for the state of Mississippi,” Balkin says. “Places that are three, four and five hours away, we can deliver both individual and even small-group activities.”

In addition, it’s less burdensome on families. “What’s wonderful is we don’t have to pull a kid out of class anymore. They can come home, get on their Chromebook or iPad, and we can provide counseling right there,” he says. “And parents don’t have to take off work, which was always a problem.”

A Love for Teaching after All?

Balkin grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas. It wasn’t an easy childhood, and he admits he could have benefited from some counseling. He had a serious seizure disorder, and his medication left him uncoordinated. He was singled out and bullied often. When he was 7, his mom signed him up for taekwondo, thinking it would help with his coordination and self-esteem.

Balkin enjoyed taekwondo immediately, although he was a bit frustrated at his slow progress. One of his three older brothers, whom he really respected, challenged him to get his black belt. That gave Balkin a goal. Today, he’s an eighth-degree black belt (ninth degree is the highest), and he also trains in Brazilian jiu-jitsu, where he holds a brown belt.

In high school, Balkin competed in taekwondo tournaments and taught kids and adults at the taekwondo studio. “It’s where I felt very different; I was treated very differently. It was kind of my haven. It was through that that I learned how to connect with people because that wasn’t happening socially for me at school,” he says.

His taekwondo teaching experience led him to pursue a teaching degree in college — where he discovered his true passion was not teaching but working with adolescents. Balkin eventually made his way back to the classroom, however, this time in higher education. Throughout his academic career, he has taught several counseling courses, particularly ones on research methods and statistics. But, as he explains, “I’m not teaching English. I’m teaching counseling. That’s a lot more fun.”