Paving the Way for Black Male Leadership

By Lisa R. Rhodes

November 2024

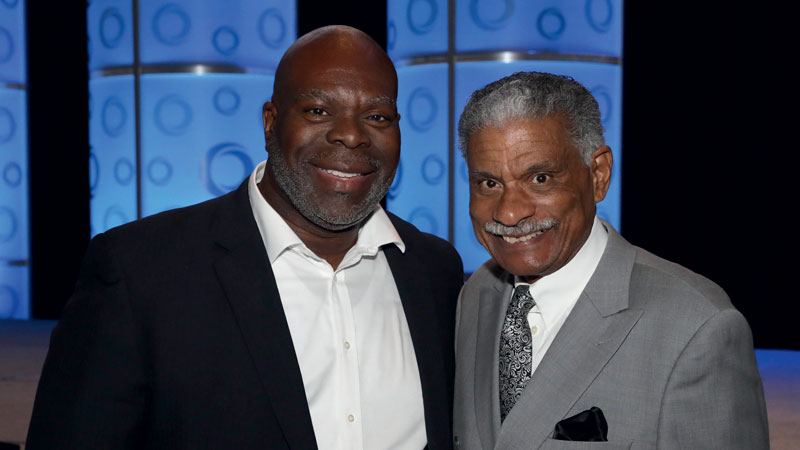

Even before Courtland C. Lee, PhD, and S. Kent Butler, PhD, LPC, embarked on a career in counseling, they were both dedicated to giving back to the Black community and lending a hand to uplift Black men.

After earning his bachelor’s degree in history and secondary education at Hofstra University in New York, Lee worked as a teacher at an elementary school in Brooklyn, New York. There, he encouraged Black and Latino boys to participate in activities that would foster a love for learning and curtail misbehaving in class.

Butler served as the assistant director of the H. Fred Simons African American Cultural Center at the University of Connecticut after completing his undergraduate studies in communications. He worked to enhance the well-being of Black students, faculty and staff and provided educational programs in the Black experience and African culture.

These early encounters opened the door to an impressive counseling career for both men. Lee entered the field after a school counselor where he taught saw his success with male students of color and suggested he pursue a graduate degree in counseling. At the encouragement of two counseling professors, Butler decided to enroll in the master’s counseling education program at the University of Connecticut, where he later went on to earn his doctorate in counseling psychology.

Leaders in the Making

Lee and Butler, both ACA Fellows, admit they never thought that decades later they would become the first two Black male presidents of ACA and that they would work to make the organization and profession more inclusive for people of color and Black men.

Lee, now a retired counselor educator and a diversity consultant in Philadelphia, served as ACA president from 1997 to 1998. Butler, a tenured professor in the Department of Counselor Education and School Psychology at the University of Central Florida, served from 2021 to 2022.

Several leaders in the field, including the late Samuel Gladding, PhD, and Tom Sweeney, PhD, approached Lee and said, “You’d be really good as ACA president. Have you ever considered running?”

“It seemed like the next logical step in terms of being able to give back to the profession and be a servant leader,” says Lee, who has written numerous books on multicultural counseling and social justice and served as editor for the Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development.

Butler says he spent years as a “worker bee behind the scenes” at ACA. Early in his career, Beverly O’Bryant, PhD, who was then-president of the Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development (AMCD), tapped him to serve as the division’s conference chair. Butler went on to help revise the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies and served as AMCD’s representative to ACA’s Governing Council.

Several of Butler’s mentors, including Lee, O’Bryant, Thomas Parham, PhD, and the late Judy Lewis, PhD, kept telling him that he needed to run for ACA president. “Ultimately, it happened for me, and I think it happened at the right time for ACA,” Butler says. “With the COVID-19 pandemic and disruption to the world that happened two years before my time as president, and with the racial strife in our country and the need for strong leadership within the organization, I feel that my presidency was right on time. During my term, I was able to accomplish a lot of things that were important to the organization, including hiring a new CEO.”

Overcoming Obstacles

Historically, the counseling profession has been a white-dominated field. Many of ACA’s leadership positions have been held by white men, especially in the beginning, Butler says. White women have also shaped the profession by serving as leaders in ACA and its divisions and regions and working as practitioners in the field and performing the operational work inside the organization, he adds.

The dearth of people of color, particularly Black men, in the profession is partly because “there are often stigmas associated with mental health disorders and therapy, and mental health may be considered taboo in marginalized communities,” Butler says. Lee and Butler agree that seeking help for mental health issues carries a stigma, particularly for Black men, who are socialized not to show signs of weakness.

Systemic racism also plays a large role. Although Lee was largely welcomed to the presidency because he had established a reputation as a thought leader in multicultural counseling through his scholarly work, he also faced a challenge that’s common for Black professionals: the need to overcome stereotypes (such as being seen as an “angry” Black man, viewed as a “diversity hire” or not considered “smart enough”).

Lee says he was able to defy these stereotypes because he had developed gravitas, a confident, self-assured demeanor. This quality, he says, helps prepare counselors for a position of leadership.

Butler ran for the presidency with the firm belief that a prospective candidate for the position doesn’t have to be a white man. “I have the ability to lead as well,” he says. “I have the know-how and expertise.”

Making the Field More Accessible

Working to make ACA and the counseling profession accessible to those who have been denied the opportunity to sit at the table was a priority for Lee and Butler during their presidencies.

Lee says one of the proudest achievements of his tenure was leading the creation of a multicultural agenda for ACA. The goal was to ensure that all of ACA’s stakeholders were on the same page to advance multiculturalism so the organization could meet the counseling and human development needs of an increasingly diverse society, he explains.

During his presidency, Butler spearheaded the Black Male Initiative, an evolving project to provide a repository and clearinghouse for evidence-based research on strength-based interventions for counseling Black men. He also supported efforts to rattle the status quo in counseling by pushing for progressive change with the hashtag #ShakeItUp.

The U.S. needs more Black male counselors to inspire Black boys to join the ranks and to help normalize discussions about mental health and the benefits of seeking therapy in the Black community, Butler says.

Lee agrees that recruiting Black men to pursue a career in counseling is essential. He argues that these efforts should begin in middle school, when they are often encouraged to consider other careers, such as medicine or law. Black men also need to be taught about options for financial assistance to pursue a degree in counseling, particularly at the doctoral level, he says.

Lee’s advice for Black men who are new to counseling is to be mindful not to get “co-opted” by working in corporate positions, such as employee assistance programs, that may offer a higher salary. Instead, he encourages these counselors to “develop a sense of social responsibility” and work in the community to help “Black males deal with the traumas that they face.”

Butler recommends Black male counselors find mentors who have their best interest at heart. He also encourages them to think outside the box, have an entrepreneurial spirit and be a good role model.

“What’s important is that all counselors work together for the betterment of Black men,” Butler says. “Our eyes need to be on the prize of obtaining racial equality, social justice, freedom and the ability to peacefully coexist in this world.”